Flexible Glass Could Make Tablets Lighter and Solar Power Cheaper

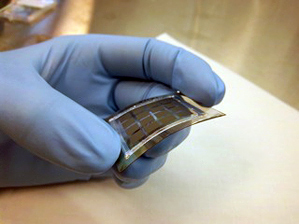

Researchers at the U.S. government’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory have built flexible solar cells using a thin and pliable kind of glass from Corning, the company that makes the glass that covers iPhone screens. The new solar cells could make rooftop solar power far cheaper.

Based on tests by Corning, which makes a product called Gorilla glass for iPhone screens and which announced the flexible material, called Willow glass, last year, shingles made from such solar cells could last for decades on a roof—even weathering hail greater than three centimeters in diameter. Conventional solar panels are heavy, bulky, and breakable, which makes them expensive to transport and install.

The new solar shingles could be nailed to a roof in place of conventional shingles. Rather than paying a roofer to put asphalt shingles on a new home, and then paying solar installers to climb back up and mount solar panels to the roof, the roofers could install solar shingles instead of asphalt ones. The only added labor cost would be hiring an electrician to plug the array of shingles into an inverter and connect it to the grid. Thin, flexible solar shingles could also be shipped more cheaply.

The cost of installation is one of the largest parts of the overall cost of solar power—its share has increased even as the cost of the cells themselves has plummeted in recent years. Indeed, installation and other auxiliary costs are now the biggest opportunity for reducing the cost of solar power. An average rooftop solar system in California costs $6.14 per watt, while solar panels themselves sell for less than $1 a watt in many cases.

Solar shingles are already available (see “Solar Shingles See the Light of Day” and “Alta Devices Plans a Fast-Charging Solar iPad Cover”). The chemical giant Dow makes them, for example. But they are typically made of plastic. Glass-based shingles, as counterintuitive as it sounds, could be more durable, says Dipak Chowdhury, division vice president and Willow glass commercial technology director at Corning. Glass is very good at sealing out the elements, which can help solar cells last for decades. It’s also surprisingly strong, and, in its flexible form, resilient. “We knew from our optical fiber work that glass is actually stronger than steel when you try to pull it apart,” he says. If Willow glass shingles were hit by hail, they would flex rather than break. While other solar shingles can also withstand hail, they may not be as good at protecting solar cells from air and moisture, he says.

The glass also makes it possible to use cadmium telluride as the solar cell material. This is the only material that’s been able to successfully challenge conventional silicon solar cells at a large, commercial scale (see “First Solar Shines as the Solar Industry Falters”). Cadmium telluride solar cells need to be made on a transparent material. Other flexible, transparent materials either can’t handle the high temperatures needed to make the solar cells, or they block too much light, reducing efficiency.

Willow glass could also be used for lighter, thinner gadgets, and even curved displays, perhaps even for a rumored iWatch from Apple (see “Mobile Summit 2013: In Smart Watch Category, Pebble Still Awaits the Big Competition”). For both flexible displays and solar cells, glass needs to be not only flexible but also very high quality, with a defect-free surface. Most glass is formed by floating a layer of molten glass on top of a molten metal, then gradually cooling it. The interaction with the metal can degrade the surface. Willow glass forms in air—a sheet forms after molten glass flows over the edges of a long trough. It is then spooled up into large rolls with special equipment that keeps the surface pristine. The defect-free surface is also key to making the glass strong, since glass is only as strong as steel if its surface is free of scratches and nicks. Once it’s scratched, it requires much less force to break. (Chowdhury says roofing tiles—as well as flexible electronics—would have to be protected from scratches with a coating of ethylene tetrafluoroethylene, or some other protective polymer.)

Using Corning’s flexible glass in solar shingles will require careful processing, much as is done now to create an iPhone display. An iPhone actually contains several pieces of glass. The touch sensor, the color filters that make up each pixel, and the millions of transistors used to control them are all produced on top of separate high-quality glass sheets. These are protected in an iPhone by Gorilla glass, which is less susceptible to scratching, but isn’t a suitable surface for transistors or other electronics. Willow glass could replace these interior sheets of glass. For rigid devices, the main advantage of doing this would be to reduce weight and display thickness—Willow glass is a third the thickness of the glass used now.

The cadmium telluride solar cells on Willow glass made at NREL were small, proof-of-concept devices that aren’t as efficient as the rigid cells now on the markets, says Teresa Barnes, a scientist at NREL. She says that in addition to improving efficiency, it will be necessary to develop ways of handling larger flexible solar cells—manufacturing equipment used now is optimized for handling flat plates of glass.

Chowdhury says another challenge will be persuading manufacturers and customers that glass solar shingles can be durable: “Sometimes perception wins over data.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.