The Anatomy of the Occupy Wall Street Movement on Twitter

The Occupy Wall Street movement began in September 2011 as a grass roots protest against the inequality, greed and corruption associated with the financial sector of the economy. The movement adopted the slogan: ”We are the 99%” which refers to the distribution of wealth in the US between the richest 1 per cent and the rest.

What was extraordinary about this movement was the speed with which it spread, passing rapidly between communities via social media and Twitter in particular.

So an interesting question is how this movement became so big, so quickly and what has happened since to the most active participants.

Today, we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Michael Conover and buddies at Indiana University in Bloomington. These guys have studied the flow of information across Twitter related to the Occupy Wall Street movement before and after the protests began. They’ve also looked at the individuals involved and how their Twitter activity has changed over this time period.

Their astonishing conclusion is that despite its fiery birth, the Occupy Wall Street movement has become a damp squib and that the key people behind it have lost interest.

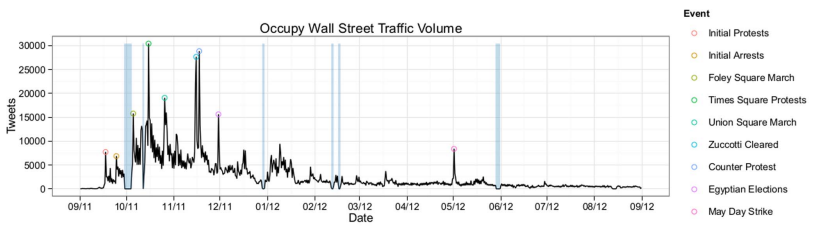

Conover and co began by studying the tweets associated with Occupy-related hashtags over a 15-month period starting three months before the protests began. That gave them a corpus of information consisting of more than .8 million tweets from almost half a million separate accounts.

They then studied a randomly chosen set of 25,000 of these users to see how their behaviour, and the network of links between them, changed throughout this time.

The results make for interesting reading. It turns out that the most vocal participants appeared to be highly connected before the movement began. They also shared a common interest in domestic politics.

But while this group became highly vocal during the movement’s peak, their engagement has dropped significantly. As Conover and co put it: “These same users, while highly vocal in the months immediately following the movement’s birth, appear to have lost interest in Occupy-related communication.”

In other words, the Occupy Walls Street movement appears to have faded away.

A significant problem is how to interpret this result. On the one hand, it would be easy to conclude that the movement has largely failed with most activists returning to life as it was before.

But Conover and co are careful to sidestep this conclusion. “An argument can be made that the movement played a role in increasing the prominence of social and economic inequality in the public discourse,” they say.

In any case, it’s unreasonably to expect that the group could have maintained the level of activity that it reached at the peak.

What it does show is how powerful the collective voice can become when it triggers the interest of a subset of users who are already connected. That’s a lesson that other activists and those they target should readily embrace.

However, Conover and co are critical of the way the movement has died away. In particular, they point to a re-occupation movement which began in May 2012 but after which engagement levels on Twitter returned to close to their previous levels within a week or so.

“It is doubtless that supporters may have hoped for a more sustained discourse than is evident from the near-complete abandonment of these once high-profile communication channels,” they conclude.

That seems harsh given that the goal of the movement was not to change the behaviour of the protesters but to change the behaviour of those in position to tackle the inequalities that triggered the movement, such as those in the financial sector and the politicians and regulators who govern them.

So an interesting follow up would be to use the same powerful microscope of social behaviour to identify this group, to study their behaviour and to see whether it has changed in a way that correlates to the Occupy Wall Street movement.

A difficult challenge but surely one worth pursuing. In the meantime, the Occupy Wall Street movement may just be sleeping.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1306.5474 : The Digital Evolution of Occupy Wall Street.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.