A Green Sahara

Today the Sahara is a vast desert spanning more than 3.5 million square miles in northern Africa. But as recently as 6,000 years ago it was a verdant landscape, with sprawling vegetation and numerous lakes. Ancient cave paintings in the region depict hippos in watering holes, and roving herds of elephants and giraffes—a vibrant contrast with today’s barren, inhospitable terrain.

The Sahara’s “green” era, known as the African Humid Period, probably lasted from 11,000 to 5,000 years ago and is thought to have ended abruptly, within one to two centuries. Now researchers at MIT, Columbia University, and elsewhere have found that this swift climate change occurred nearly simultaneously across the rest of North Africa.

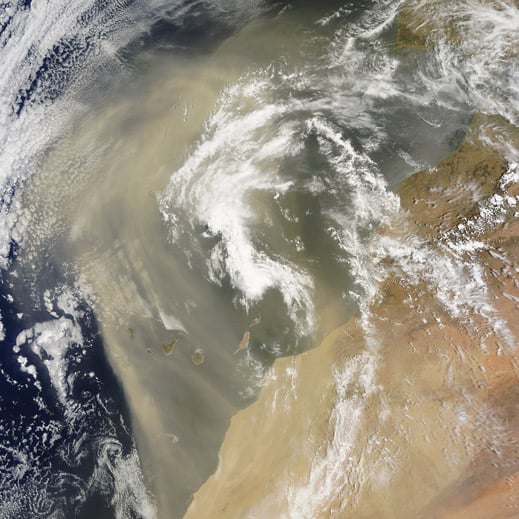

The team traced the region’s wet and dry periods over the past 30,000 years by analyzing sediment samples collected off the coast of Africa. Such sediments are composed, in part, of dust blown from the continent over thousands of years. The more dust that accumulated in a given period, the drier the continent may have been.

From their measurements, the researchers found that the Sahara emits five times more dust today than it did during the African Humid Period. Their results, which suggest a far greater change in Africa’s climate than previously estimated, are published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

David McGee, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, says the quantitative results of the study will help other scientists determine the influence of dust emissions on both past and present climate change.

“Our results point to surprisingly large changes in how much dust is coming out of Africa,” says McGee, who did much of the work as a postdoc at Columbia. “This gives us a baseline for looking further back in time, to interpret how big past climate swings were.”

As a next step, McGee is working with collaborators to test whether these new measurements may help resolve a long-standing problem: the inability of climate models to reproduce the wet conditions in North Africa 6,000 years ago. With results that can be used to estimate the impact of dust emissions on regional climate, models may finally be able to replicate the North Africa of that era—a region of grasslands that were host to a variety of roaming wildlife.

“This is a period that captures people’s imaginations,” McGee says. “It’s important to understand whether and how much dust has had an impact on past climate.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.