On August 12, 1948, Senator Bourke Hickenlooper learned something that horrified him: the details of the American nuclear program were about to be spilled to a roomful of foreign scientists. He sped into action, requesting an emergency meeting with the secretary of defense. “Some of the most vital of our weapons secrets were about to be disclosed in full,” he later recounted. He and the secretary moved quickly to stop the man they believed responsible.

That man was Cyril Stanley Smith, ScD ‘26. Three years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet Union had begun vying for nuclear supremacy, escalating fears of atomic warfare. Even allies such as Britain and the United States had only just loosened some restrictions on the exchange of scientific information. According to the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, that exchange could not include specifics about the development of American nuclear technology. Yet somehow, Smith had been authorized to visit a British research center and discuss “the basic metallurgy of plutonium.”

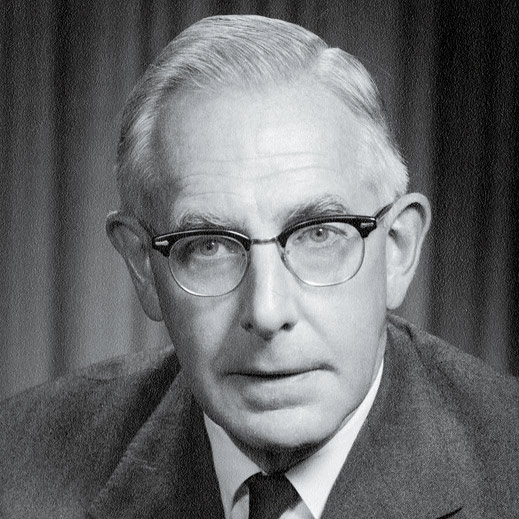

Smith was no double agent. Though British by birth, he was a naturalized American citizen, educated at MIT, who would later return as a professor after making his name as a metallurgist. An expert on the properties of uranium and plutonium, he began working on U.S. atomic energy projects in 1943.

“I remember the three years at Los Alamos as the most exciting in my whole life,” Smith wrote about his work on the Manhattan Project. In retrospect, he was slightly ashamed at how little thought he and fellow scientists had given to the human consequences of their research. The atmosphere of Los Alamos had been intoxicating: it was a time, he wrote, when “as rarely before, new discoveries in materials actually controlled the pace of larger events.”

After the war, Smith taught at the University of Chicago, founded its Institute for the Study of Metals, and served as an advisor to the Atomic Energy Commission from 1946 until 1952. It was two years into that term that he unknowingly touched off a political scandal.

Senator Hickenlooper, a Republican from Iowa, recounted the colorful tale of the “Cyril Smith incident” at a congressional hearing in 1950. When Hickenlooper heard that Smith was going to England to meet with British scientists, the senator alerted Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, who agreed that Smith had to be stopped from disclosing vital military information. But Smith had left two weeks before.

Sumner Pike, the acting chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, phoned Smith’s sister, with whom he’d been staying, but Smith had gone off to Scotland and was not expected back in England until the following day. U.S. officials sent multiple messages. One telegram read: Refer letter from Fisk July 26 STOP Commission believes item six outside agreed area technical cooperation and should not be discussed STOP If already begun should be discontinued STOP Please advise if conversations begun = US Atomic Energy Commission.

While Hickenlooper grew anxious in Washington, Smith and his family were vacationing on the Isle of Skye. The flurry of communication that greeted him when he finally returned, he would later write, struck him as reflecting “a routine change of opinion” rather than an urgent directive. He did, however, recall hearing a “sigh of relief” when a Washington official reached him by phone and learned that

Smith had not yet met with the British scientists; in fact, he had no idea that anyone else was even interested in what he considered a low-priority, unofficial visit.

Smith had been instructed to discuss the basic metallurgy of plutonium with British scientists, but what the senator imagined as a revelation of the country’s most secret atomic science, Smith thought of as no more than a discussion with peers about one element in the periodic table. He later wrote that he’d never intended to speak of plutonium’s use in bomb construction. To a metallurgist like Smith, the British and American decision to ease some restrictions on scientific communication merely provided a happy occasion to catch up on the metallurgical happenings on the other side of the Atlantic.

Smith was no doubt amused that a Congressional hearing (to which he was not invited) devoted more than two hours to hashing out the details of the “incident.” At the hearing, Hickenlooper and several colleagues emphasized the perceived threat of the incident and Pike’s role in it. Although other senators maintained that Pike was merely a scapegoat, he ended up being held responsible for authorizing Smith’s trip, which may have contributed to the decision to block his confirmation as permanent chairman. The “Cyril Smith incident” had real-world consequences after all, but never for Smith himself.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.