Going Under

Since the mid-1800s, doctors have used drugs to induce general anesthesia in patients undergoing surgery. However, little is known about how these drugs create such a profound loss of consciousness.

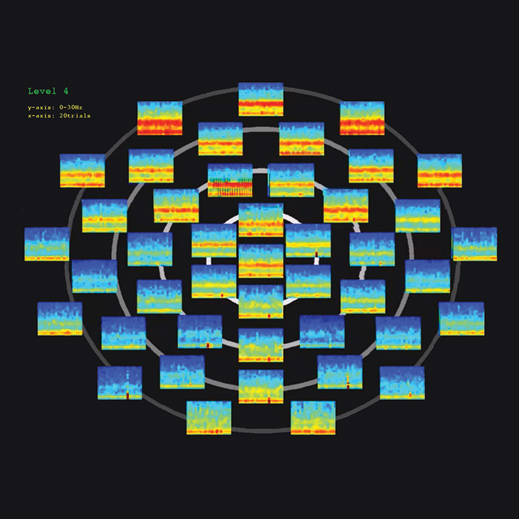

In a recent study that tracked brain activity in human volunteers over a two-hour period as they lost and regained consciousness, researchers from MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) identified distinctive brain patterns associated with different stages of general anesthesia. Those brain-wave signatures could help anesthesiologists better monitor patients during surgery and make sure they don’t wake up.

Such unintended waking occurs once or twice in 10,000 operations, says Emery Brown, an MIT professor of brain and cognitive sciences and health sciences and technology, who is also an anesthesiologist at MGH.

“It’s not something that we’re fighting with every day, but when it does happen, it creates this visceral fear, understandably, in the public,” he says. “And anesthesiologists don’t have a way of responding, because we really don’t know when you’re unconscious.”

Anesthesiologists now rely on a monitoring system that converts electroencephalogram (EEG) information into a single number between 0 and 100. However, the researchers say, that index actually obscures the information that would be most useful.

In the new study, Brown and Patrick Purdon, an instructor of anesthesia at MGH and Harvard Medical School, worked with colleagues to monitor subjects as they received propofol, a common anesthestic. As the subjects began to lose consciousness, the EEG showed that brain activity in the frontal cortex oscillated in both the low-frequency (0.1 to 1 hertz) and alpha-frequency (8 to 12 hertz) bands. The researchers also found a specific relationship between the oscillations in those two frequency bands: alpha oscillations peaked as the low-frequency waves were at their lowest point.

When the brain reached a slightly deeper level of unconsciousness, a marked transition occurred: the alpha oscillations flipped so their highest points occurred when the low-frequency waves were also peaking.

As the researchers slowly decreased the dose of propofol to bring the subjects out of anesthesia, they saw that brain activity patterns flipped again, so that the alpha oscillations were at their peak when the low-frequency waves were at their lowest point.

Purdon and Brown are now starting a training program at MGH that will help doctors interpret EEG information to better monitor how deeply a patient is anesthetized.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.