Islands and the CounterIntuitive Effect They Have on Tsunamis

Islands close to a coast can provide significant protection from waves. For that reason, coastal communities often thrive in areas that are protected by nearby islands.

But what happens in the event of a tsunami? There is a long-standing belief that tsunamis are most destructive when they hit long, straight coastal stretches. So it’s natural to assume that nearby islands may offer significant protection by acting as natural barriers.

But there is some anecdotal evidence that, far from protecting coastal areas, islands may actually amplify the devastating effect of a tsunami. And oceanologists have long known that tsunamis behave very differently from wind-generated waves. Nevertheless, convincing scientific evidence about the way tsunamis interact with islands is thin on the ground.

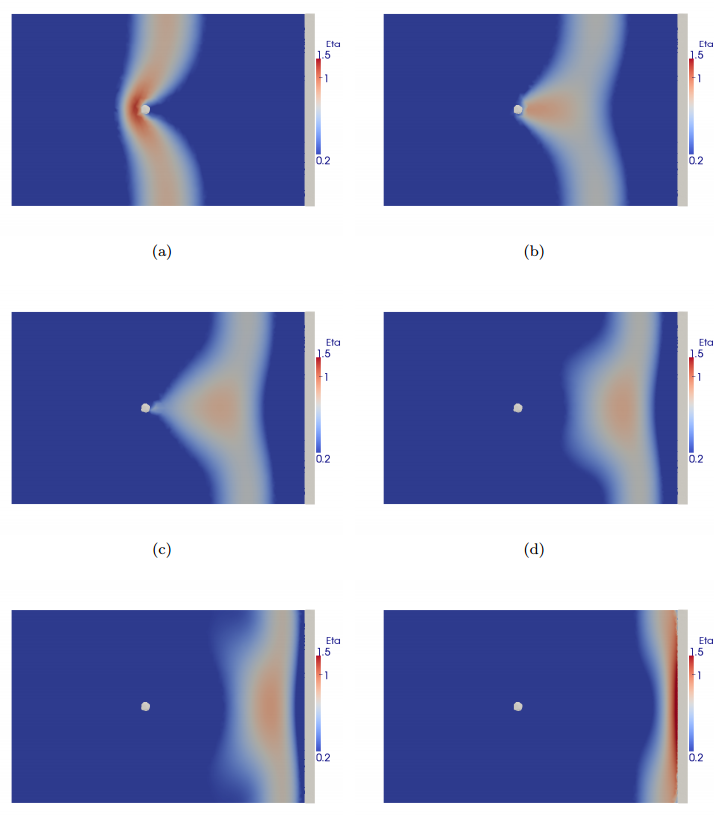

Today that changes thanks to the work of Themistoklis Stefanakis at University College Dublin and friends at the Ecole Normale Superieure Cachan in France, who have simulated the effect that islands have on tsunamis and how this changes the impact of the tsunami on a straight beach behind.

This kind of computer simulation is by no means simple. Stefanakis and co simplified the problem by considering the presence of a small conical island some hundred metres high in front of a straight stretch of beach several kilometres behind it.

One of the big challenges for computer scientists doing this kind of work is to perform the simulation accurately but with minimal computational cost.

One problem is that the cost of a simulation increases dramatically with the complexity of the model. Stefanakis and co cope with this by taking data from a specially selected set of points in the model rather than from all over it.

What’s more, they use a learning algorithm to examine the experimental results from one simulation and then use this to fine tune the selection of data points in the next simulation, an approach known as “active experimental design”.

Another challenge is knowing when to finish a simulation. Without a so-called stopping criterion, the computer simulation just keeps on going and this inevitably increases the computational cost. So Stefanakis and co have paid special attention to developing useful stopping criteria that halt the simulation when its gaols have been achieved.

The team’s results will serve as a powerful warning to many coastal communities. “After running 200 simulations, we have found that in none of the situations considered did the island offer protection to the coastal area behind it,” they say.

On the contrary. In many situations, small islands dramatically amplified the effect of a tsunami for the beach behind. “The maximum amplification achieved was 70 per cent more than were the island absent,” say Stefanakis and co.

So coastal communities that are protected from wave-generated winds by nearby islands are at serious risk from tsunamis.

This kind of work should allow early warning systems to be put in place in these areas and for local communities to be educated about the extra risks that they face. And recent experience of tsunamis in Indonesia and Japan show that you can never be too prepared for such a disaster.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1305.7385 : Can Small Islands Protect Nearby Coasts From Tsunamis? An Active Experimental Design Approach

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.