Game Theory and the Treatment of Cancer

“A small but growing number of people are finding interesting parallels between ecosystems as studied by ecologists (think of a Savanna or the Amazon rain forest or a Coral reef) and tumours.” So begin David Basanta and Alexander Anderson at the Moffitt Cancer Centre in Florida in a fascinating paper describing a new way of thinking about cancer and the way to treat it.

They point out that it’s more or less impossible to understand any creature or its behaviour without thinking carefully about the environment in which it lives and evolves. “As convenient as it would be for cancer biologists to study tumour cells in isolation, that makes as much sense as trying to understand frogs without considering that they tend to live near swamps and feast on insects,” say Basanta and Anderson . What would biologists make of a frog’s sticky tongue without knowing how it is used for catching flies, for example?

Similarly, how should cancer biologists think about cancer cells capable of producing vascular endothelial growth factor, a protein that promotes the growth of blood vessels?

Clearly, the importance of this protein only makes sense when thinking about a cancer cell’s environment: how close it is to blood vessels that it can exploit, for example.

Today, Basanta and Anderson show how this new ecological view of cancer should dramatically change the way cancer specialists treat the disease in the coming years.

They point out that ecologists have gained deep insight into the way specific ecosystems allow many different plants, animals, bacteria and so on, to co-exist.

In particular, they have looked at how invading species can change this balance, sometimes dramatically altering the ecosystem in the process.

That’s not unlike the way certain cancers occur. Specialists have long known that invading viruses and bacteria can change the balance in healthy tissue causing it to become cancerous. Other changes, such as the formation of mutant cells, can do the same. The new thinking is that in these scenarios the environment is a crucial factor in the development of cancer.

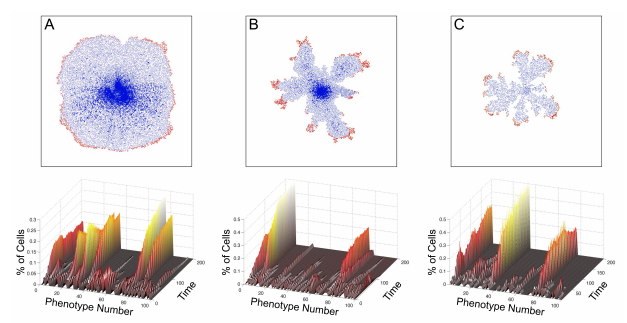

Ecologists have a powerful mathematical approach called evolutionary game theory for studying these delicate balances. This shows how certain combinations of creatures, a small number of predators among a large number of prey for example, settle down into evolutionary stable strategies but also how others form systems that are highly unstable.

The key idea here is that the long-term outcome does not depend on the size of the populations is involved but on the way they interact.

Basanta and Anderson say that many lessons can be learnt from thinking about cancer in this way. “One crucial lesson, especially when used to understand cancer evolution, is that focusing on indiscriminately destroying as many cancer cells as possible is not necessarily the best thing to do for a patient,” they say. That’s especially if this approach leaves some of the cancer cells intact.

The reason is that the total number of cancer cells is much less important than the way they interact–evolutionary game theory clearly shows a small populations can grow dramatically.

According to this idea, a better approach would be to change the way the cells interact with each other and their environment. One idea is that this could be used to allow a less aggressive form of cancer to evolve, which would be less harmful to the patient.

There is some evidence that this does indeed work. For example, researchers have shown that giving lung cancer patients a cancer vaccine called p53 before treating them with chemotherapy is significantly more successful than giving the treatments the other way round. This may be an example of exactly the kind of result that evolutionary game theory predicts.

While all this is easier said than done there are reasons to be sanguine. Basanta and Anderson point out that the ecological view of cancer does not compete with conventional approaches but compliments them. “This will lead to a better understanding of the biology of cancer and to new and improved therapies,” they conclude.

That’s certainly an optimistic conclusion but not one entirely borne out by the experiences that ecologists have had in attempting to manipulate and save natural ecosystems. Nevertheless, the ecological approach will provide insight and that will surely be an important benefit for researchers and patients in future.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1305.2249: Exploiting Ecological Principles To Better Understand Cancer Progression And Treatment

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.