Participants in Personal Genome Project Identified by Privacy Experts

One of the biggest questions in biology is the nature versus nurture debate, the relative roles that genetic and environmental factors play in determining human traits.

In 2006, George Church at Harvard University and a few others started the Personal Genome Project (PGP) to help answer this question. The goal is to collect genomic information from 100,000 informed members of the public along with their health records and other relevant phenotypic data. The idea is to use this information to help tease apart the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors.

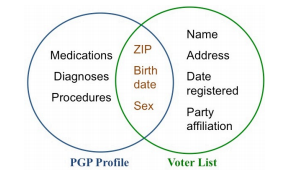

The project does not guarantee privacy for those who sign up. Indeed, the participants can reveal as much information as they like, including their ZIP code, birth date and sex.

However, the data is ‘de-identified’ in the sense that the owners names and addresses are not included in their profiles on the PGP website and this generates a veneer of privacy.

Today, Latanya Sweeney and colleagues at Harvard show that even this is practically useless in keeping owners identities private. They say a relatively simple comparison of the list of PGP participants with other databases such as voter lists reveals the identity of a significant number of them with remarkable accuracy.

The de-anonymisation procedure is simple. Voter lists contain information including name, address, but also zip code, birth date and sex. So it is straightforward to compare this list with PGP participants who have also included their zip code, birth date and sex.

When there is a match, the question is whether the zip, birth date and sex uniquely identify an individual. Sweeney has argued in the past that it does with an accuracy of up to 87 per cent, depending on factors such as the density of people living in the zip code in question.

These results seem to prove her right. Sweeney and co-submitted the results to the PGP organisation and asked them to check how accurate the de-anonymisation process had been. It turns out they accurately identified people with a success rate of up to 97 per cent.

This kind of vulnerability is well-known. “Our ability to learn their names is based on their demographics, not their DNA, thereby revisiting an old vulnerability that could be easily thwarted with minimal loss of research value,” say Sweeney and pals.

They point out that the way to solve this problem is to include birth dates and zip codes that are less precise, giving just a year of birth or the general area of residence, for example.

This isn’t so easy to change on the PGP website so the team have created a freely available editing tool that allows any participant to modify his or her details on the website in a way that reduces the chance of identification.

(Sweeney and co also point out the obvious tactic of removing identifying names from information attached to a participant’s profile, which they found in a significant proportion of entries.)

That should make the Personal Genome Project significantly more private for those who choose this option. It should also serve as a warning for future projects involving personal data that privacy isn’t always as easy to protect as it might at first seem.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1304.7605: Identifying Participants in the Personal Genome Project by Name

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.