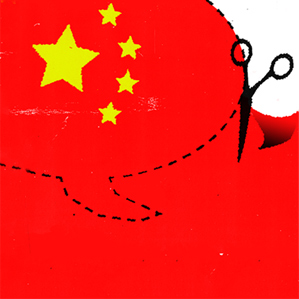

Social Media Censorship Offers Clues to China’s Plans

In February last year, political scandal rocked China when the fast-rising politician Bo Xilai suddenly demoted his top lieutenant, who then accused his boss of murder, triggering Bo’s political downfall.

Gary King, a researcher at Harvard University, believes software he developed to monitor government censorship on multiple Chinese social media sites picked up hints days earlier that a major political event was about to occur.

Five days before Bo demoted his advisor, the Harvard software registered the start of a steady climb in the proportion of posts blocked by censors, a trend that lasted for several days. King says he has noticed similar patterns several times in advance of major political news events in the country. “We have examples where it’s perfectly clear what the Chinese government is about to do,” he says. “It conveys way more about the Chinese government’s intents and actions than anything before.”

King has seen dissidents’ names suddenly begin to be censored, days before they are arrested. A jump in the overall censorship rate, like the one that foreshadowed Bo’s fall, also presaged the arrest of artist Ai Weiwei in 2011. The rate declined in the days before the Chinese government announced a surprise peace agreement with Vietnam in June 2011, defusing a dispute over oil rights in the South China Sea. King suspects those patterns show that censors are being used as a tool to dampen and shape the public response to forthcoming news. That tallies with his other findings that censors focus on messages encouraging collective action rather than just blocking all negative comments.

China’s social media censorship is less well known, and less understood, than the system known as the Great Firewall, which blocks access to foreign sites, including Facebook and Wikipedia, from inside the country. But social media censoring is arguably as important to the country’s efforts to control online speech. Social media is attractive in a country where conventional media is tightly controlled, and the Great Firewall directs that interest toward sites under government direction.

Studies like King’s tracking which posts disappear from social media services in China have now begun to reveal how the country’s censorship works. They paint a picture of a sophisticated, efficient operation that can be carefully deployed to steer the nation’s online conversation.

The most popular social media services in China are microblog networks, or “weibos,” roughly equivalent to Twitter and used by an estimated 270 million people, according to government figures. In China, all microblog service providers must establish an internal censorship team, which takes directions from the government on filtering sensitive posts. Sina Weibo and Tencent Weibo between them claim the majority of active users, and are said to have censorship teams as large as 1,000 people.

Those teams can act fast, as a study of 2.38 million posts on Sina Weibo (12 percent were censored) showed last year. “It’s minutes or hours, not days,” says Jed Crandall, an assistant professor at University of New Mexico, who took part in research with colleagues from Rice University and Bowdoin College. Previous studies had only checked for deleted posts at intervals of a day or more, says Crandall, who concludes that assumptions that social network censorship was largely manual were incorrect. “There must be some automation tools that would help them, or they wouldn’t be able to do the rate that we observed.”

Crandall has also uncovered evidence of how Chinese censorship is used to steer the direction of public conversation rather than just being used to block out sensitive topics for good. His software saw censors successfully dampen the online outcry after a major train crash in July 2011 before carefully relenting once politicians had managed to shift public chatter onto more favorable terms. “It demonstrates the kind of PR that the censors are trying to pull off,” says Crandall. “They delay the discussion until the news cycle changes—when the conversation changes to a favorable one, people can talk all they want.”

Other research shows that censorship can be driven by more than just the content of a post. A study published by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University last year analyzed 56 million messages from Sina Weibo. That study revealed that the location a person posts from can affect the chances of that post being censored. Approximately half of all posts from Tibet and the neighboring region of Qinghai that used known sensitive words were deleted, while just over 12 percent of posts from Beijing and Shanghai using terms from the list were censored.

Nele Noesselt, a researcher at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies in Hamburg, recently surveyed Chinese government attitudes to social media and concluded that the Communist party has come to see them as a route to popular political legitimacy. Visibly responding to public opinion—even if online opinion has been filtered by censors—can keep citizens happy. (Noesselt notes that government participation in social networks has also soared; official figures claim there are 80,000 government accounts.)

That’s not to say that China has the social Web fully under control. Online conversations on China’s social networks are as chaotic and rapidly evolving as they are outside the Great Firewall. Dissent still exists on weibos, as users invent code words to talk about censored topics. However, the findings of King, Crandall, and others make it clear that studying censorship could be very useful to anyone trying to figure out what the Chinese government’s priorities, concerns, and plans are.

Crandall is currently working with the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, which monitors global human rights through digital media, on tracking the political trends and goals of weibo censorship.

King is continuing his own research, and his ideas also caught the eye of a U.S government agency after he published results online last year, he says. That agency, which he declines to identify, invited him to Washington to speak about his work. It later sought contractors to build censorship-tracking software of its own, says King. He isn’t familiar with its intended use, but says that China’s sophisticated, ever-changing social media censorship is plainly a valuable signal. “If I was negotiating with the Chinese government,” he says, “I would want our graphs there on the wall.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.