First Enzyme-Based Memory Created in the Lab

Electronic processors are highly efficient at certain types of computation. For example, a standard PC can vastly outperform any human at arithmetic. However, computer scientists have long been fascinated by the ability of biological systems to do tasks, such as face recognition, at speeds and a power efficiency that put the most powerful supercomputers to shame.

Clearly, biology is able of computing in ways that traditional processors have failed to capture, which is why there is a significant interest in unconventional methods of computing that explore new ways of processing information.

One form of unconventional computing is biochemical and involves using molecules to encode information and using chemical reactions to process it. Nature has developed highly complex machinery for doing this so much of the focus has been on exploiting biological molecules for this task, using proteins, DNA and the like.

Today, Vera Bocharova and a few pals at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York, say they ‘ve used a set of enzymes to create a memory system that can “learn” to produce a specific output given a certain input. They says this system can even “unlearn” again later. “We report the first realization of a simple variant of associative memory in an enzymatic biochemical process,” they say.

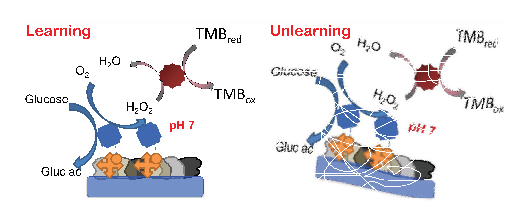

The theory is straightforward. Imagine the system as a black box that can have two chemical inputs and a chemical output. This output is a chemical called oxidised 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB).

The black box produces oxidised TMB when it receives input 1 but the goal is to make it produce oxidised TMB when it receives input 2. In other words, Bocharova and co aim to “teach” the system to produce oxidised TMB when it senses input 2.

The trick they’ve perfected is one of chemistry. Input 1 alone produces oxidised TMB. But Bocharova and co have designed the chemistry so that when input 1 and 2 are added together, the result is a chemical environment that is ripe for the production of oxidised TMB–but only when they add more of input 2.

So having added input 1 and 2 together–having “trained” the system–it is now ready to produce oxidised TMB when it receives input 2 alone. The system has “learned” to respond to input 2.

It can later “unlearn” by changing the chemical conditions again.

(The chemical details of inputs 1 and 2 are in the paper referenced below.)

That’s an impressive result, not least because memory systems like this could be connected in a kind of chemical network to work as a sensor or as an information storage device, for example. “This research offers interesting possibilities of incorporating bio-inspired, memory elements in designs aimed at increasing the complexity of biomolecular computing systems,” they say.

Just how such systems might outperform conventional computers isn’t yet certain but they could, for example, be made to function in environments that are utterly alien for conventional processors.

Of course, this research is a long way from any kind of functioning device. But these kinds of computational building blocks give a fascinating glimpse into the potential for unconventional computing to change the way we might think about information processing in future.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1304.5731: Realization of Associative Memory in an Enzymatic Process: Towards Biomolecular Networks with Learning and Unlearning Functionalities

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.