Regaining Lost Brain Function

How do you make an electronic brain prosthesis that could restore a person’s ability to form long-term memories? Recent experiments by Theodore Berger and his colleagues, including Sam Deadwyler at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and researchers at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, have begun to describe how it might be done.

Last year, the team showed that an implant that records the activity of one set of neurons and directs the activity of another can replace lost brain function in monkeys. The researchers used an array of electrodes to measure the electrical activity of neurons in the animals’ prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in decision making that directs many types of cognitive responses associated with memory. Five monkeys were trained to perform a memory task in which they were shown an image on a screen and then had to use hand movements to steer a cursor to that image when they were subsequently shown a collection of clip-art pictures.

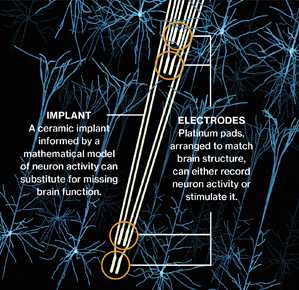

The monkeys’ neural activity was recorded by a tiny ceramic-enclosed electronic device and relayed to an external computer. In the first part of the experiment, the researchers analyzed the brain activity they had recorded from the cortex. But then came the hard part. Memory is formed when one set of neurons processes the signals from another set, but how can you replicate this processing in an electronic device? First, you have to figure out the code the brain is using. From the initial recordings, the research team was able to extrapolate what’s called a MIMO model—short for multi-input/multi-output. This type of mathematical model can characterize the neural firing patterns detected by the electrode implant and, after processing the patterns, spit out the signals that instruct other neurons to form the appropriate memory.

To demonstrate that their model worked, the researchers gave the monkeys cocaine. The cocaine-addled monkeys had trouble remembering the correct image. But with the implant in place and the MIMO model translating the incoming signals and feeding data back to another set of neurons, they were able to pick out the right picture about as reliably as usual, if not slightly more so.

But how could a doctor replace a brain function, such as the ability to form long-term memories, that someone had already lost? In that case, it wouldn’t be possible to simply mimic a previous example of how the individual’s brain worked and duplicate it in the electronic device. However, preliminary work suggests that a recording from a healthy person’s brain could be used in the injured or sick. “We’ve recorded from a number of rodents and were able to derive a generic model for certain kinds of processing,” says Deadwyler. The research team will need to see if the same rules apply to primates. If they do, it might mean that a MIMO model could be used to form “a generic pattern that would resemble the kind of processing most of us do with respect to certain kinds of tasks,” says Deadwyler.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.