Novel Heating System Could Improve Electric Car’s Range

Buyers considering an electric car must bear in mind that using battery-powered heating and air conditioning can decrease the car’s range by a third or more (see “BMW’s Solution to Limited Electric-Vehicle Range: A Gas-Powered Loaner”). A New York Times reviewer recently ran into this problem on a test drive, ending up stranded with a dead battery (see “Musk-New York Times Debate Highlights Electric Cars’ Shortcomings”).

But a heating and cooling system under development almost eliminates the drain on the battery. The researchers are working with Ford on a system that they hope to test in Ford’s Focus EV within the next two years. The work is being funded with a $2.7 million grant from the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Energy.

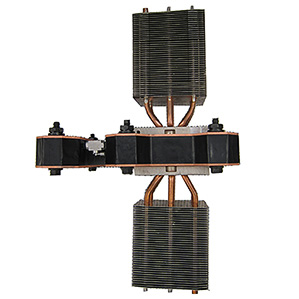

The researchers describe their new device as a thermal battery. It uses materials that can store large amounts of coolant in a small volume. As the coolant moves through the system, it can be used for either heating or cooling.

In the system, water is pumped into a low-pressure container, evaporating and absorbing heat in the process. The water vapor is then exposed to an adsorbant—a material with microscopic pores that have an affinity for water molecules. This material pulls the vapor out of the container, keeping the pressure low so more water can be pumped in and evaporated. This evaporative cooling process can be used to cool off the passenger compartment.

As the material adsorbs water molecules, heat is released; it can be run through a radiator and dissipated into the atmosphere when the system is used for cooling, or it can be used to warm up the passenger compartment. The system requires very little electricity—just enough to run a small pump and fans to blow cool or warm air.

Eventually the adsorbant can’t take in any more water, but the system can be “recharged” by heating the adsorbant above 200 °C. This causes it to release the water, which is condensed and returned to a reservoir.

An electric heater could be used for this purpose, says Evelyn Wang, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, who is leading the work. “But there so many sources of heat, such as heat from a solar water heater—so electricity wouldn’t have to be used,” she says. Fully recharging the system is expected to take about four hours, which is about what it takes to recharge some common electric vehicles at standard charging stations.

The basic concept behind the temperature control system isn’t new (see “Using Heat to Cool Buildings”). But it’s been difficult to make such a system compact enough for use in a car, especially because separate containers are normally used for evaporating and condensing the coolant. The researchers’ more compact design uses one container for both purposes.

The researchers are now developing materials that can adsorb more water, which would make it possible to use less adsorbant. One is a modified zeolite, a type of porous material that has long been used in catalysis. They’re also working on a material called a metal organic framework, whose properties can be systematically changed by varying the composition of organic materials that link microscopic clusters of metal. The researchers have added highly thermally conductive materials such as carbon-based nanomaterials to their adsorbant so the system can heat and cool more rapidly, which can also make it possible to shrink its overall size.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.