LED Lights to Cut 60-Watt Bulb to Five Watts

Philips has cut the amount of power of its overhead LED tube light in half, a sign of continuing improvements in LED lighting geared at displacing incumbent technologies.

The company says it has built a prototype of a tubular overhead LED light that produces 200 lumens of light with a watt of power. Its current products produce light at 100 lumens per watt, about the same as florescent tube lights. Even though the price of LEDs will be higher, Philips thinks that they can start to displace more of the florescent tube lights that are everywhere from office buildings to parking garages based on energy savings.

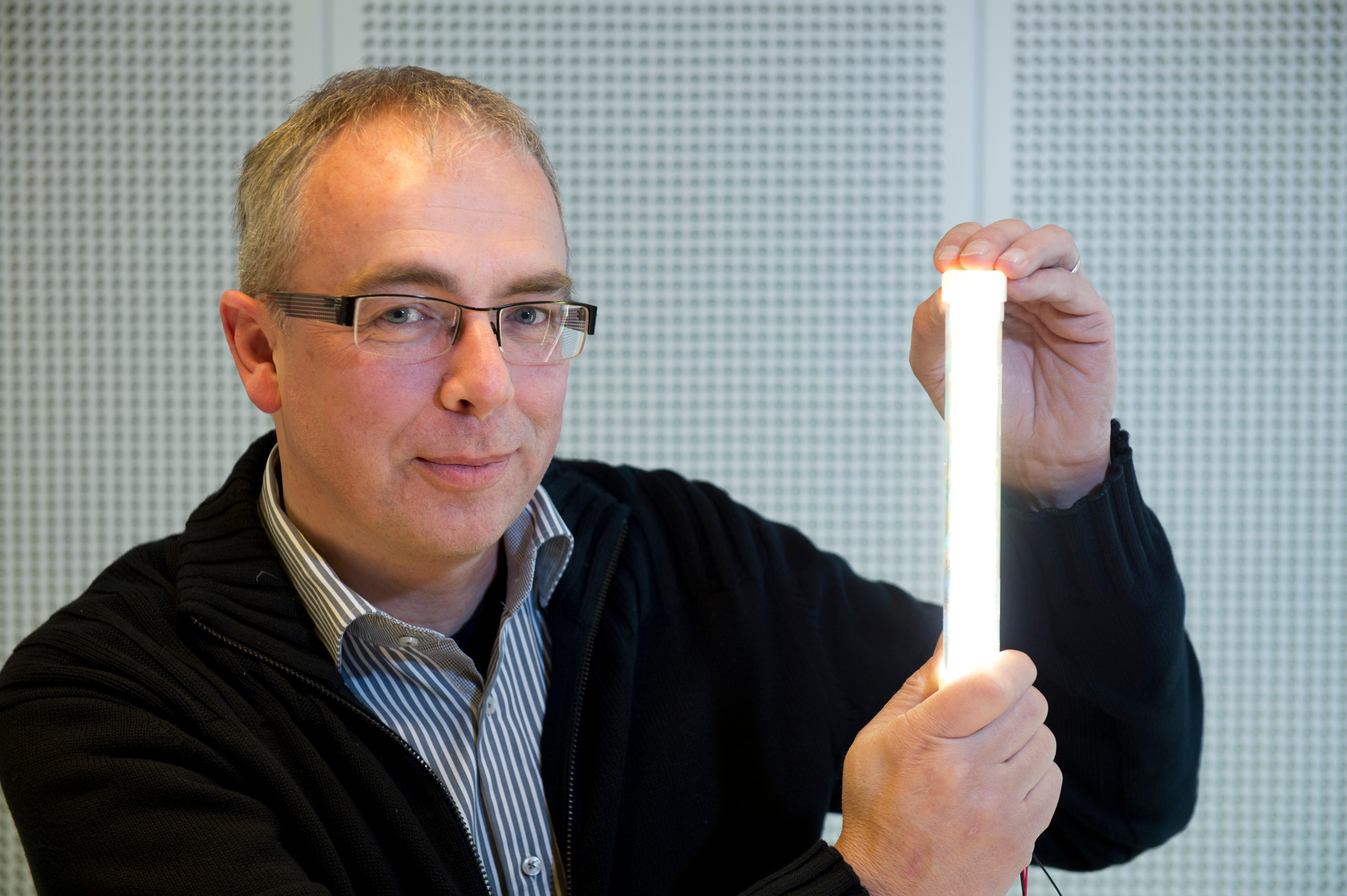

The company plans to commercialize the technology in 2015 and transfer it to other products, including consumer light bulbs. In a consumer LED light bulb, that would mean that a 60-watt replacement would consume about 5 watts. “You could easily see how it will work through the entire retrofit line,” says Coen Liedenbaum, the innovation area manager in lighting at Philips Lighting. (See, How to Choose an LED Light Bulb.)

Engineers were able to get the jump in efficiency by tuning the light the lamp gives off. The LED semiconductor and the phosphor – the coating material that converts blue LED light to white light – have been optimized for how people perceive brightness. “We are trying to exactly match the eye sensitivity of people, therefore needing less energy to perceive the same level of brightness,” Liedenbaum says. The optics and other components were also improved for efficiency.

In labs, lighting engineers have been to achieve well over 200 lumens per watt for some time. And Cree late last year said it developed a 200-lumens-per-watt commercial LED for bright outdoor applications. Philips was able to achieve that efficiency at a warm temperature of 2700 Kelvin – the color mostly associated with incandescent bulb light—which is technically more challenging, says Liedenbaum. The color rendering index (CRI), a measure of light quality, is expected to be well above 80, as good as many lighting products.

By targeting the ubiquitous tubular light, the replacement LED could have a massive impact on energy consumption. Still, LED lighting makers need to further improve efficiency and lower per-lumen costs for mass appeal. And industry executives say that that the rate of efficiency improvement in conventional LED semiconductors is slowing down. In response, LED lighting companies are pursuing different strategies to improve performance.

Startup Soraa is producing spotlights with LEDs made from gallium nitride on a gallium nitride substrate, which improves the conversion of electricity to light. Most LEDs are made on sapphire because it’s less expensive. (See, Soraa Pushes LED Brightness to Next Level.) Another approach to is to lower production costs. Bridgelux plans to start producing gallium nitride LEDs on silicon substrates, a way to take advantage of existing silicon wafer manufacturing fabs.

To get better performance with its LED tubular light, Philips used a number of design tricks but Liedenbaum says the company’s LED division is also looking at alternative LED materials.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.