Network Theory Approach Reveals Altitude Sickness to be Two Different Diseases

Acute mountain sickness–or altitude sickness–is that common feeling of headache, dizziness, sleep disturbance and so on, that many people experience when travelling from lowland to high altitude.

For most people, the symptoms gradually wear off but for an unfortunate few, the disease can become life-threatening. So a quick, accurate diagnosis followed by appropriate treatment is crucial.

Today, Kenneth Baillie at the University of Edinburgh and a few pals say that acute mountain sickness is actually two different diseases, rather than one. It may even be more than two. What’s interesting about their approach is that they used network theory to analyse the correlations between symptoms from a large number of people. The clusters in this network correspond to different diseases they say. The result could have an important impact on the way these diseases are treated and for the outcomes for victims

Baillie and co asked some 300 travellers to high altitudes in Bolivia and Kilimanjaro to fill out a questionnaire about their symptoms giving details about the severity of any headaches they experienced as well as any tiredness, sleep disturbances and so on.

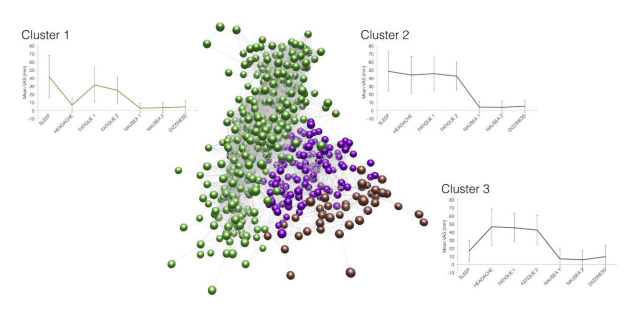

They then mapped out the correlations between the various symptoms, creating a network. An increasingly standard tool in network theory these days is cluster detection–the ability to spot parts of a network that are more strongly linked together than others.

Baillie and co say they used just such a technique to reveal three distinct patterns of symptoms. In particular, they say that sleep disturbance and headache are commonly reported without the other. “This is consistent with the hypothesis that distinct pathogenetic mechanisms underlie sleep disturbance and headache at high altitude,” say the team.

That’s an interesting result that also makes medical sense. There is mounting evidence that headaches and sleep disturbances are caused by different mechanisms. For example, headaches in those suffering from altitude sickness seem to be caused by factors such as fluid retention and tissue swelling in the brain. Sleep disturbance, on the other hand, seems to be related to breathing problems.

So treating each separately should make the future diagnosis and treatment of acute mountain sickness much more accurate.

But the bigger picture is that this kind of network approach to symptoms could have broader application. A data driven approach to biology–or bioinformatics, as it is called–is standard in the analysis of gene expression and other molecular networks. There’s no reason why it couldn’t be used to gain insight into the nature of conditions that currently labour under umbrella terms, such as autism, and which involve many complex symptoms.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1303.6525: Network Analysis Reveals Distinct Clinical Syndromes Underlying Acute Mountain Sickness.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.