A Cheaper Way to Make Hydrogen from Water

One of the main barriers blocking wide-scale use of fuel cells is the expensive catalysts used to produce hydrogen fuel from water. Researchers at the University of Calgary say they have developed a novel method for making catalysts using inexpensive metals.

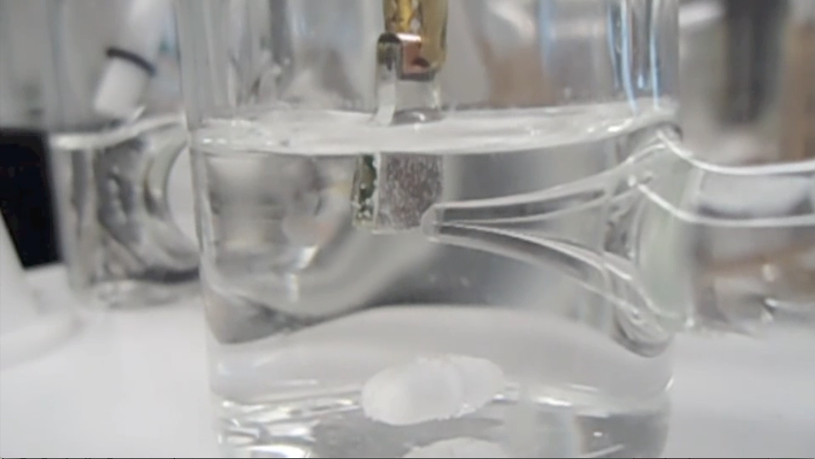

Two chemistry professors—Curtis Berlinguette and Simon Trudel—today published a paper in Science showing how their electrocatalysts perform as well as more expensive materials. They have patented their production method and have formed a company called FireWater Fuel which plans to have a product available as early as next year. The goal is to make an electrolyzer—a device that splits water to make hydrogen and oxygen fuels—that is affordable enough for businesses and consumers.

Their invention is making catalysts from a combination of metals compounds that use iron, cobalt, and nickel. The process, which treats metal compounds or oxides with light, doesn’t require high temperatures.

“The discovery in our paper is the ability to make catalyst films with a uniform distribution of multiple metals,” Berlinguette says. “We use a technique that uses light to decompose environmentally benign precursors in air into our catalytic films. The process is scalable and translates to almost every metal in the periodic table.”

Conventional catalysts are made with rare or expensive metals, such as platinum. The Calgary researchers’ method produces films that are amorphous in their molecular shape, rather than a crystalline structure. That highly disordered structure actually makes them more reactive.

Harvard professor Daniel Nocera, while at MIT, introduced a low-cost catalyst made of an amorphous cobalt oxide for splitting water to make hydrogen fuel. A company called Sun Catalytix was formed in 2009 using venture and government funding to commercialize his work but it has struggled to make a viable product and has since shifted its focus to making flow batteries. (See, Sun Catalytix Seeks Second Act with Flow Battery.)

Berlinguette says he and Trudel have advanced previous work because their process can be used on any metal on the Periodic Table and combines multiple metals. “Amorphous heterogeneous catalysts are well known,” he says. “The problem is that it is difficult to make amorphous materials with many other metals (than cobalt oxide) and it is infinitely more difficult to introduce multiple types of metals into amorphous films.”

A commercially viable electrolyzer is considered a key component to the long-sought hydrogen economy. A good catalyst can lower the amount of electricity that is needed to produce hydrogen and oxygen from water. The hydrogen would then be stored in tanks and fed into fuel cell to produce electricity as needed.

Initially, FireWater Fuel intends to develop an electrolyzer to produce hydrogen for energy storage at wind farms. It intends to create a commercial prototype of a freezer-size electrolyzer that would convert a few liters of water a day to electricity for consumers by 2015.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.