A Stealthy De-Extinction Startup

Two of biotechnology’s most prolific and far-sighted researchers say they’re teaming up to start a company that intends to rewrite the rules of animal reproduction.

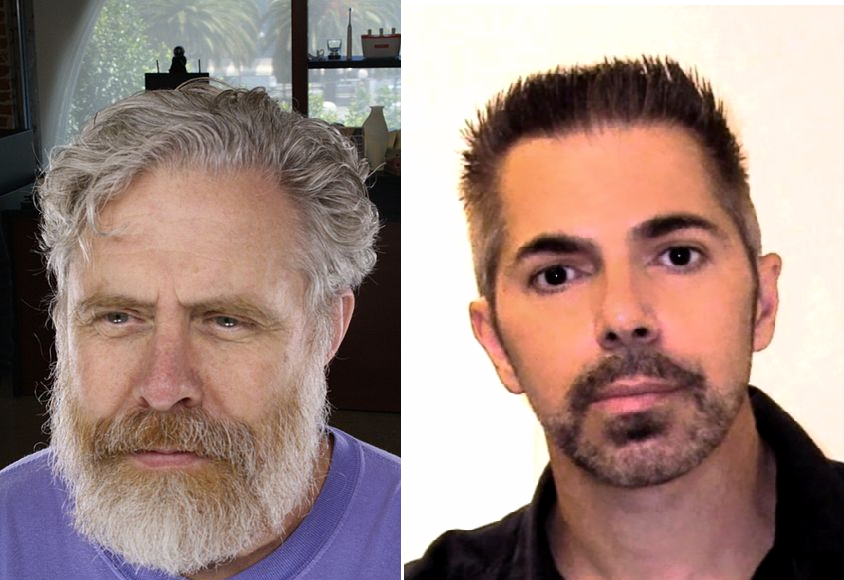

The company, provisionally named Ark Corporation, is being cofounded by stem-cell pioneer Robert Lanza and Harvard Medical School DNA expert George Church.

I heard about the startup last Friday at TEDx DeExtinction, a gathering of conservationists and molecular biologists interested in bringing wooly mammoths, Tasmanian tigers, and other extinct species back to life (see “An Unlikely Plan to Revive the Passenger Pigeon”).

It’s interesting stuff. Who wouldn’t want to see a saber-toothed tiger?

But here’s the deal: the very same biotechnologies needed to reanimate lost species are going to have far, far greater financial and social impact when they’re applied to commercial breeding of livestock, pets, and even humans.

“There are just so many downstream implications,” says Lanza, who is chief scientific officer of Advanced Cell Technology, a stem cell company.

Ark, he says, hopes to help revive some extinct species, including a Spanish mountain goat. But the company’s real aim is to combine cutting-edge cell biology and genome engineering in order to breed livestock and maybe even create DNA-altered pets that live much longer than usual. “Imagine a dog that lives 20 years,” he says.

Before I heard about Ark, I would never have imagined a collaboration between Church and Lanza, who are a couple of the most entrepreneurial and far-out dudes in biotech. It was a bit like learning that Elon Musk and Donald Trump plan to build a space station together.

While I didn’t find out who else is involved in Ark, or where its financing will come from, Lanza promised me the startup will have the backing of “top human IVF clinics” and leading cattle-breeding operations.

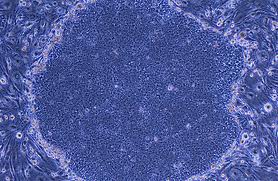

Ark’s key technology is going to be induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells (see “Growing Heart Cells Just for You”). To make iPS cells, researchers take an ordinary skin cell and, by modifying it or adding certain chemicals, turn it into a potent stem cell that’s able to grow into any other tissue of the body, including eggs and sperm.

It’s exactly this ability to make sperm and eggs in the lab that opens the commercial possibilities Lanza and Church say their startup company will exploit.

Many farm animals, like pigs and cows, are already created from sperm collected from prize sires and then frozen and shipped around the world. If companies could make sperm in a bioreactor instead, they’d have a factory able to take over the job of the world’s blue-ribbon steers, boars, and roosters. They could even keep making sperm once those animals die.

Beyond farm animals, iPS cells have even more mind-boggling possibilities in human reproduction. With this technology, it may be possible to create functional eggs and sperm for people who are infertile because of age or other issues.

What’s more, with iPS cells, it’s at least theoretically possible to make eggs from a man’s skin cell, or sperm from a woman. In other words, the technology could one day let two men, or two women, have children that share both their genes. I’m pretty sure no one on Noah’s Ark thought of that.

Trust me, Lanza and Church have. The use of iPS cells for human reproduction (as well as for saving extinct animals and just generally creating “animals of a desired genetic make-up”) is all described in patent applications on file at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office in Lanza’s name.

When I raised this idea with Church, he cautioned that it’s still too early to talk about the application of iPS cells in human reproduction. “It’s not part of the company. And if it were, we wouldn’t be saying it,” he assured me.

Even among commercial cattle breeders, lab-brewed sperm and eggs might be a bit controversial. Will the technology be accepted? Will iPS offspring be healthy?

That’s where extinct animals come in. Trying out some of these methods to bring back extinct species would be a way to find out if they work, not to mention a way to generate huge publicity coups involving furry, friendly faces.

Last week, during that TEDx event in Washington, D.C., Lanza and Church offered to help Spanish scientists revive the Pyrenean ibex, or bucardo, a mountain goat extinct since 2000. Lanza says he also wants to help restore the passenger pigeon. As there are no living passenger pigeons, scientists would be required to extensively modify the genome of a closely related species.

“We will make iPS cells from a band-tail pigeon, splice in passenger pigeon DNA, then try to make sperm and maybe eggs,” Lanza said.

But the real business of Ark Corporation will be commercial reproduction of farm species. Church calls the duo’s offers to help revive extinct species more of “a good will thing, to show that we are interested in helping conservation as well as agriculture.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.