First Graphene Audio Speaker Easily Outperforms Traditional Designs

Most loudspeakers work using a diaphragm that creates pressure waves in air by mechanically vibrating. “For human audibility, an ideal speaker or earphone should generate a constant sound pressure level from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, i.e. it should have a flat frequency response,” say Qin Zhou and Alex Zettl who are both at the University of California, Berkeley.

Today, these guys unveil an earphone-sized speaker that more or less matches this requirement. What’s unusual about this speaker is that the diaphragm is made from a few layers of graphene, the carbon chicken-wire material that is revolutionizing everything from transistor design to particle physics experiments.

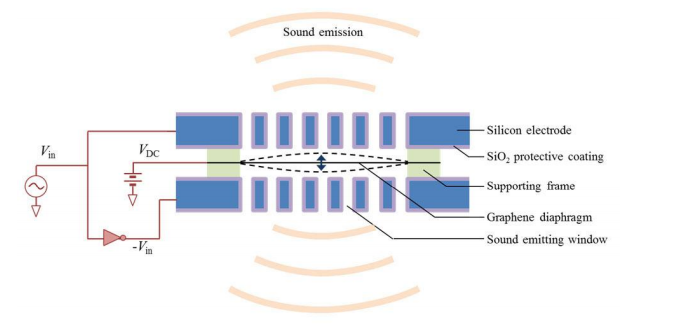

The new speaker is simple. It consists of a graphene diaphragm sandwiched between a couple of electrodes that create an electrical field. When this field oscillates, it causes the graphene to vibrate too and this generates sound.

What’s extraordinary about the new device is its performance. “The graphene speaker, with almost no specialized acoustic design, performs comparably to a high quality commercial headset,” says Zhou and Zettl.

The reasons are straightforward. The diaphragm in any speaker is essentially a simple harmonic oscillator with an inherent mass and restoring force that determine the way it vibrates at different frequencies. Most diaphragms need to be damped to broaden the range of frequencies over which they perform. But, as Zhou and Zettl point out, “damping engineering” quickly becomes complex and expensive and produces inevitable power inefficiencies.

One way to reduce the amount of damping engineering required is to make the diaphragm very thin and light with a small spring constant so that the air itself damps its motion. But that has always been a tricky prospect given how weak and fragile most materials become when they are thin.

That’s why graphene is the ideal candidate. “It is electrically conducting, has extremely small mass density, and can be configured to have very small effective spring constant,” say Zhou and Zettl. And, of course, it’s also very strong.

These guys have created a speaker using a thin film of graphene just 30 nm thick and 5mm in diameter as the diaphragm. And they’ve compared its performance to a conventional Sennheiser MX-400 earphone with promising results. “Even without optimization, the speaker is able to produce excellent frequency response across the whole audible region (20 Hz~20 KHz), comparable or superior to performance of conventional-design commercial counterparts,” they say.

That’s a handy result. Best of all, the air-damped graphene converts most of its energy into sound and so is extremely energy efficient. That’ll be useful for mobile devices in which energy consumption is crucial

So it’s not hard to imagine that earphones using graphene will be available in the short term and may come to dominate the market in the long term. Worth keeping an ear open for.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.2391: Electrostatic Graphene Loudspeaker

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.