The Puzzle of Ancient Star Catalogues and Modern Brightness Corrections

Ancient star catalogues that give both the position and magnitude of stars date back many centuries. The most famous and influential was compiled by Ptolemy around 140 BC and contains listings for 1028 stars. Modern astronomers have long admired the accuracy with which Ptolemy measured the position of stars but have paid surprisingly little attention to the magnitudes.

That changes today thanks to a study by Bradley Schaefer at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Schaefer has analysed the magnitudes in Ptolemy’s ancient star catalogue and compared them to modern values, find them to be extremely accurate.

But he has another finding that is puzzling: Ptolemy’s magnitude are not just accurate, they are also corrected for the fact that a star appears brighter overhead than it does near the horizon, a phenomenon called extinction. “This is startling and without precedent,” says Schaefer.

The physics behind extinction is straightforward. Starlight has to travel a certain distance through the atmosphere to reach an observer, a process that causes scattering and absorption. This distance is minimised when the star is overhead. However, the light from a star close to the horizon has to travel more than twice as far through the air and this dramatically increases the amount of light lost. For this reason, stars that are low in the sky can appear more than a magnitude dimmer than they really are.

The explanation would have been unknown to Ptolemy (it was only formulated in this way in 1729). So an interesting question is how Ptolemy could have corrected his observations. Unfortunately, the ancient astronomer offers no clues in his own writing. While he devotes some time to explaining how to measure position with the help of an armillary, he says nothing about the process he used to measure magnitude.

Schaefer says there are several ways that Ptolemy could have performed the trick. For a start, the magnitude of a star is a relative measurement so ancient astronomers must have picked one star as a reference and then looked for others with a similar brightness, just as modern astronomers do the job.

From a given observing position, some stars would regularly reach the zenith or close to it while others would never get higher than a few degrees above the horizon. And yet Ptolemy gets their relative brightnesses correct.

One idea Schaefer puts forward is that the measurements for all stars would have been done when they were close to the horizon so that they all suffered from the same level of extinction. Another is that observers would have corrected more or less subconsciously for the dimming since they would have had long experience of it.

He has been able to rule out several potential suggestions, such as the possibility that his result is a fluke, a possibility that he says he can rule out with his statistical analysis.

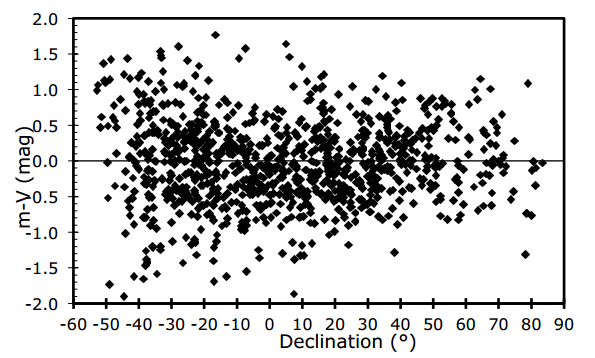

The mystery deepens with another of Schaefer’s discoveries that Ptolemy consistently overestimated the correction for extinction in some directions and underestimated it in others although overall, the average correction for extinction was exactly right. Why this might have been, Schaefer has no idea.

Curiously, Schaefer says he has found similar extinction corrections in the star catalogues compiled by Al Sufi working (c 960 AD) in Isfahan in what is now Iran, and in the records of Tycho Brahe (c1590) who has working on the island of Hven in the straights between Denmark and Sweden. Neither describe in any detail how they measured magnitude.

Clearly these ancient astronomers had powerful techniques for correcting their data that have since been lost. Suggestions for how they might have done it in the comments section please.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1303.1833 : The Thousand Star Magnitudes In The Catalogues Of Ptolemy, Al Sufi, And Tycho Are All Corrected For Atmospheric Extinction

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.