An Autopsy of a Dead Social Network

Friendster is a social network that was founded in 2002, a year before Myspace and two years before Facebook. Consequently, it is often thought of as the grand-daddy of social networks. At its peak, the network had well over 100 million users, many in south east Asia.

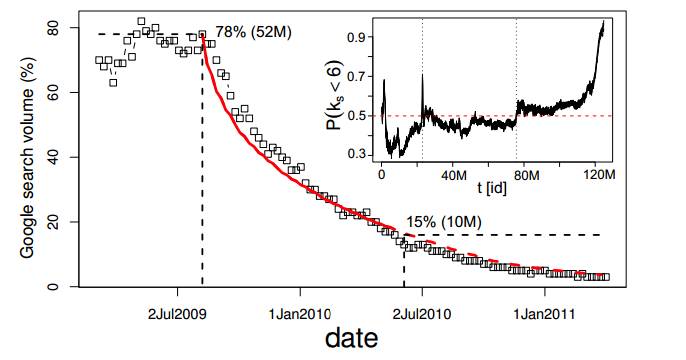

In July 2009, following some technical problems and a redesign, the site experienced a catastrophic decline in traffic as users fled to other networks such as Facebook. Friendster, as social network, simply curled up and died.

This is the company that famously turned down a $30m buyout offer from Google in 2003.

(Friendster has since been rebranded as a social gaming platform and still enjoys some success in south east Asia.)

The question, of course, is what went wrong. Today, David Garcia and pals at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, give us an answer of sorts. These guys have carried out a digital “autopsy” on Friendster using data collected about the network before it gave up the ghost.

They say that when the costs–the time and effort–associated with being a member of a social network outweigh the benefits, then the conditions are ripe for a general exodus. The thinking is that if one person leaves, then his or her friends become more likely to leave as well and this can cascade through the network causing a collapse in membership.

But Garcia and co point out that the topology of the network provides some resilience against this. This resilience is determined by the number of friends that individual users have.

So if a big fraction of people on a network have only two friends, it is highly vulnerable to collapse. That’s because when a single person exits, it leaves somebody with only one friend. This person is then likely exit leaving another with only one friend and so on. The result is a cascade of exists that sweeps through the network.

However, if a large fraction of people on the network have, say, ten friends, the loss of one friend is much less likely to trigger a cascade.

So the fraction of the network with a certain number of friends is a crucial indicator of the network’s vulnerability to cascades.

Garcia and co examined this fraction–they call it k-core distribution–for networks such as Friendster, Myspace and Facebook and the results are telling. “We find that the different online communities have different k-core distributions,” they say.

Of course, communities that are vulnerable in this way don’t automatically fail. Before that can happen, the cost-to-benefit ratio must drop to a level that makes individuals likely to leave. It is the combination of a low cost-to-benefit ratio and a vulnerable k-core distribution that is fatal for social networks.

Garcia and co say, in particular, that in the months before the collapse of Friendster, the cost-to-benefit ratio dropped dramatically as a result of design changes and technical problems.

So in this digital autopsy, the cause of death was a drop in the cost-to-benefit ratio. “This measure can be seen as a precursor of the later collapse of the community,” they conclude. But a contributing factor was also the k-core distribution.

There are clearly lessons here for today’s online social communities. Indeed, the collapse of Friendster has more than a passing resemblance to the collapse of Digg, a social news aggregator, following design changes that presumably altered the cost-to-benefit ratio for its users. However, if Garcia and co are right, its k-core distribution must also have been a contributing factor.

Facebook and other social networks ought to be paranoid about this kind of problem, if they’re not already. It’s not hard to imagine how botched design changes could send people away, particularly if there is another emerging network ready to pick up the slack.

In 2009, Facebook is thought to have benefited from Friendster’s collapse. It’s far from unlikely that Facebook itself will one day be a victim of a similar set of circumstances.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1302.6109: Social Resilience in Online Communities: The Autopsy of Friendster

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.