Microchip Restores Vision

A wirelessly controlled microchip has restored limited vision to patients in a small experimental trial, report researchers in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The German medical technology company Retina Implant developed the artificial retina, which was implanted in one eye of each participant as part of a company-funded trial. The patients had all been blinded by retinitis pigmentosa or another inherited disease that cause the eye’s light-detecting rod and cone cells, called photoreceptors, to degenerate and die over time. In theory, the device could also benefit patients with degenerative eye diseases such as macular degeneration, says Katarina Štigl, a clinical scientist and ophthalmologist at the University of Tübingen, who led the study.

With the implant, eight of the nine patients in the trial could perceive light. Five were able to detect moving patterns on a screen as well as everyday objects such as cutlery, doorknobs, and telephones. Three were able to read letters. Seeing their own hands and the faces of their loved ones had the biggest impression on the patients, says Štigl. “The very personal things, such as if a mouth is smiling, or the shape of a nose, are the most exciting for them,” she says.

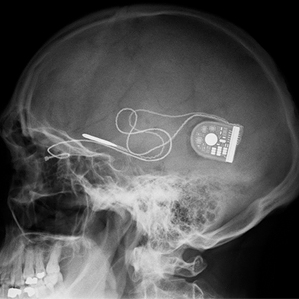

The implanted device consists of a three-millimeter-square chip with 1,500 pixels. Each pixel contains a photodiode, which picks up incoming light, and an electrode and an amplification circuit, which boosts the weak electrical activity given off by the diode. A thin cable that runs through the eye socket connects the implant to a small coil implanted under the skin behind the ear, which means most of the system is invisible. The coil under the skin is powered by an external battery pack that can be held behind the ear with magnets.

The results follow an announcement earlier this week from California-based Second Sight that its Argus II system was approved for use in the United States (see “Bionic Eye Implant Approved for U.S. Patients”). The two technologies take different approaches to restoring vision in patients with retinal degeneration. In Second Sight’s system, a camera mounted on eyeglasses picks up images that are converted into electrical signals by a small wearable computer. That data is then sent to a 60-electrode chip to stimulate neurons in the retina. The Retina Implant device instead attempts to directly replace the lost photoreceptors, allowing the remaining retinal circuitry to do the data processing.

More than 20 groups worldwide are working on some form of visual prosthesis, says Joseph Rizzo, a neuro-ophthalmologist with Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Harvard Medical School, who is also developing an artificial retina. “Every design has its advantages and disadvantages,” he says. Because the Retina Implant system uses photodiodes, it was necessary to include a power supply, which means the system is not self-contained around the eye, he says.

Each patient in the study had a different experience with the implant. One experienced no benefit, while another could read letters on restaurant signs and store names; another could recognize stopping and moving cars at night from their headlights. Štigl says these results can be influenced by many factors, including whether other cells in the eye have degenerated and where the chip is placed in the retina.

The company is now testing its device in Germany, the U.K., and China and is still recruiting patients.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.