How “Bullet Time” Will Revolutionise Exascale Computing

The exascale computing era is almost upon us and computer scientists are already running into difficulties. 1 exaflop is 10^18 floating point operations per second, that’s a thousand petaflops. The current trajectory of computer science should produce this kind of capability by 2018 or so.

The problem is not processing or storing this amount of data–Moore’s law should take care of all that. Instead, the difficulty is uniquely human. How do humans access and make sense of the exascale data sets?

In a nutshell, the problem is that human senses have a limited bandwidth–our brains can receive information from the external world at roughly gigabit rates. So a computer simulation at exascale data rates simply overwhelms us. The famous aphorism compares data overload to drinking from a fire hose. This is more like stopping a tidal wave with a bucket.

The answer, of course, is to find some way to compress the output data without losing its essential features. Today, Akira Kageyama and Tomoki Yamada from Kobe University in Japan put forward a creative solution. These guys say the trick is to use “bullet time”, the Hollywood filming technique made famous by movies like The Matrix.

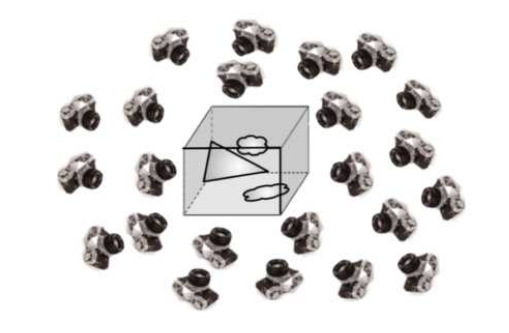

Bullet time is a special effect that slows down ordinary events while the camera angle changes as if it were flying around the action at normal speed. The technique involves plotting the trajectory of the camera in advance and then placing many high speed cameras along this route. All these cameras then film the action as it occurs.

This footage is later edited together to look as if the camera position has moved. And because the cameras are all high speed, the footage can be slowed down. The results are impressive, as anyone who has seen the Matrix movies or played the video games can attest.

Kageyama and Yamada say the same technique could revolutionise the way humans access exascale computer simulations. Their idea is to surround the simulated action with thousands, or even millions, of virtual cameras that all record the action as it occurs.

Humans can later “fly” through the action by switching from one camera angle to the next, just like bullet time.

All this sounds computationally complex but it is actually a useful way to compress the data. The compression arises because each camera records a 2-dimensional image of a 3-dimensional scene.

Kageyama and Yamada say that the footage from a single camera can be compressed into a file of say 10 megabytes. So even if there are a million cameras recording the action, the total amount of data they produce is of the order of 10 terabytes. That’s tiny compared to the exascale size of the simulation.

These guys have tested the idea on the much smaller scales that are possible today. They simulated the way seismic waves propagate in a 10 GB simulation. They used 130 virtual cameras to record the action and compressed the resulting movies to 1.7 GB. “Our movie data is an order of magnitude smaller,” they say, adding: “This gap will increase much more in larger scale simulations.”

That’s an interesting and exciting idea that could have big implications for the way we access “big data”. In fact, it’s not hard to imagine the film and gaming industries that inspired the idea, embracing it for future productions. And 2018 isn’t far away now.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1301.4546: An Approach to Exascale Visualization: Interactive Viewing of In-Situ Visualization

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.