1366 Technologies Tries to Break the Solyndra Curse

BEDFORD, Mass.–A small solar startup opens a new factory and gets ready to tap a Department of Energy loan guarantee with the hopes of competing with global manufacturers. This may sounds like the second coming of Solyndra, but the story of 1366 Technologies so far is very different.

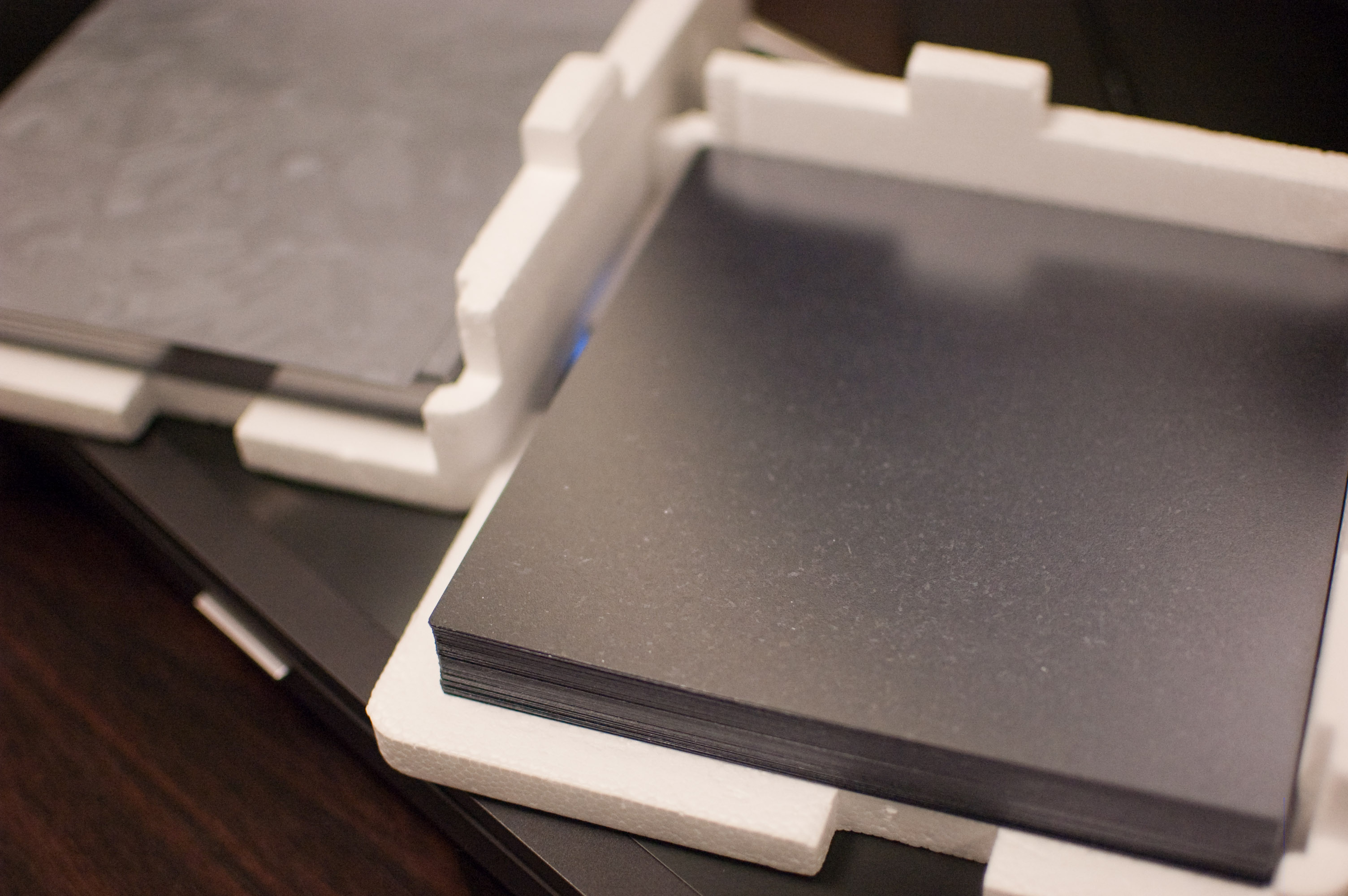

1366 Technologies yesterday opened a demonstration plant here where it will manufacture wafers, the thin square sheets of silicon that are converted into cells, which are then wired together to make a solar panel.

By solar industry standards, the plant will be very small—able to produce 25 megawatts worth of solar power per year. But it’s significant because it will put 1366 Technologies’ cost-saving technology to test in a manufacturing environment. If 1366 Technologies can perfect its novel wafer-making machine here, it will effectively remove remaining technical risk and, with financing, be able to build a planned one-gigawatt-per-year plant.

The traditional process of making wafers, where wafer slices are sawed from large ingots of very pure polycrystalline silicon, is complex and wastes lots of expensive material. At this plant, 1366 Technologies will be making wafers at half the cost and produce wafers for cells with about the same efficiency—17 percent. It plans to start making wafers for sale to cell manufacturers within 18 months using a fully automated process, says chief technology officer Ely Sachs, a former MIT professor who co-founded the company almost five years ago.

Building a full-scale plant to make wafers will require about $200 million and 1366 Technologies plans to tap a DOE loan guarantee for about half of that amount, says Craig Lund, the company’s vice president of business development.

Any clean energy company that uses a DOE loan guarantee will immediately draw comparisons to Solyndra, the infamous California-based solar startup that went bankrupt after taking out more than $500 million in loans. (See, A Solar Startup that Isn’t Afraid of Solyndra’s Ghost.)

But both in its technology and business strategy, 1366 Technologies has taken a very different route to the DOE loan. First and foremost, 1366 Technologies has been frugal—having raised $47 million so far, compared to several hundred million dollars at Solyndra—and is taking a measured approach to scaling up, rather than rush into high-volume production.

Whereas Solyndra had a highly specialized thin-film solar product that ultimately didn’t keep pace with the price of commodity silicon solar panels, 1366 Technologies is making a product that fits into the existing solar supply chain—a silicon wafer. Because silicon prices have plummeted in the past four years, 1366 Technologies’ Direct Wafer technology is less compelling than it was when the company launched. Still, executives are confident that they will find customers because they can offer meaningful cost reductions, despite a brutal solar industry shake-out. (See, The Dog Days of Solar.)

The company has also formed partnerships, through investments, with large energy companies, including Hanhwa Solar and NRG Energy. This will help it get access to capital and potential customers.

1366 Technologies certainly can’t be declared a financial success. It must work out any technical issues and prove it can deliver a lower-cost product that will attract customers. If it does, the company will be able to show that innovation in manufacturing can contribute to the economy and help bring down the cost of solar.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.