Computer Scientists Measure How Much of the Web is Archived

Museums and libraries have long attempted to preserve cultural artifacts for future generations. Given that the internet is a cultural phenomenon of extraordinary variety and influence, it’s no surprise that archivists are turning their attention to preserving it for future generations.

That’s no easy task given the rate at which new pages, pictures, videos and audio recordings appear and disappear from the online world. So an interesting question is how much of the web they’ve so far managed to save.

Today, Scott Ainsworth and a few pals from Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, give us an answer of sorts. They say it depends on how and what you count because different online sources seem to be archived in wildly different ways.

These guys begin by explaining that it’s simply not possible to gather data on every online object that ever existed. “Discovering every URI that exists is impossible,” say Ainsworth and co.

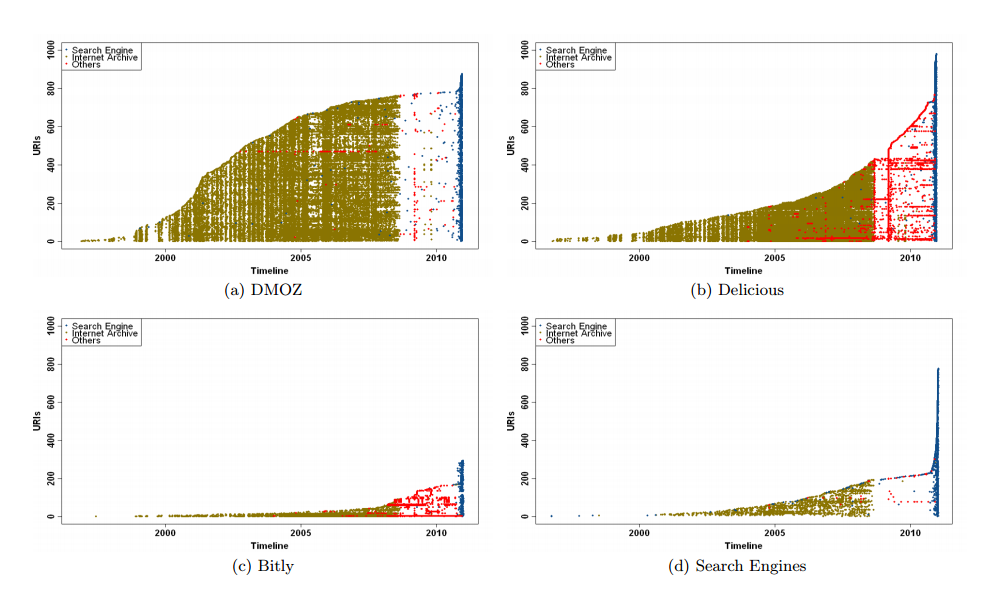

Instead they take a statistical approach by gathering a sample of online addresses and then seeing what percentage of them have archived copies. Ainsworth and co sampled 1000 web addresses from the Open Directory Project (DMOZ), from the Delicious Recent Bookmark List, from the URL shortening service, Bitly, and from the search engines Google, Bing and Yahoo.

They then looked for archived versions of all these addresses using Memento, an aggregator of internet archive sources such as the Internet Archive, Archive-It, The National Archives and so on. (Ainsworth is one of the developers of Momento).

Finally, they counted the percentage of addresses that have been archived, the number of times each had been archived and how far back the archives went.

The results show some interesting variation. The Internet Archive clearly has the best coverage and depth say Ainsworth and co. That’s not surprising given that it is the oldest and best known of the web archives.

Search engines also keep cached versions of every page they index but only for a month or so. The other archives tend to be specialist facilities which keep good archives but only for a small subset of the internet. For example, The National Archives is the UK government’s official archive.

The amount of archiving also depends on the source. Addresses taken from DMOZ and Delicious are all relatively well archived, particularly in the recent past when search engine caches record up to 90 per cent of these sites.

The same cannot be said of addresses taken from Bitly or search engines where the archiving is woeful. Ainsworth and co say the difference probably arises from the fact that people have to submit addresses to DMOZ and Delicious, whereas addresses from search engines are gathered automatically, leading to various biases.

Bitly is particularly bad with less than a third of addresses being archived. Just why it performs so badly is a mystery. “The low archival rate leads us to think that many private, stand-alone, or temporary resources are represented,” suggest Ainsworth and co.

So the answer to the question: “how much of the internet is archived?” is mixed. The proportion of the web that has at least one archived copy varies between 35 and 90 per cent depending on the source. Clearly some parts of the web are being preserved at an impressive rate. And yet other parts are being lost, presumably forever.

Of course, it’s not possible to know how serious this loss will turn out to be. But if future generations are to be given an insight into the cultural forces at work on Earth in the early 21st century, archivist will have to be ever more vigilant in recording our online existence.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1212.6177 :How Much of the Web Is Archived?

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.