Sociophysicists Discover Universal Pattern of Voting Behaviour

One of the triumphs of statistical physics is that it explains how seemingly complex behaviour emerges from the simple actions of large numbers of individual agents.

In recent years, physicists have begun to apply this idea to the social sciences. The idea is to explain the complex behaviour of societies using the simple actions of individuals, a discipline known as sociophysics. The ability to simulate this behaviour has provided a powerful way to test these ideas in areas ranging from crowd dynamics to financial markets.

One area that has attracted particular interest is voting patterns, for which high quality data is available in many countries around the world. That’s allowed sociophysicists to test an interesting hypothesis–that people in countries with the same electoral rules should vote in exactly the same way. Or in other words, that the distribution of votes for candidates should be the same in all countries which share the same electoral system.

The first studies of this question produced ambiguous results. That’s probably because researchers treated candidates from all parties as equal. However, various researchers have argued that this isn’t fair because the number of votes a candidate receives depends in large part on the popularity of his or her party.

A better idea, they say, is to compare candidates in the same party so that the differences between the number of votes they receive should largely depend on their own activities.

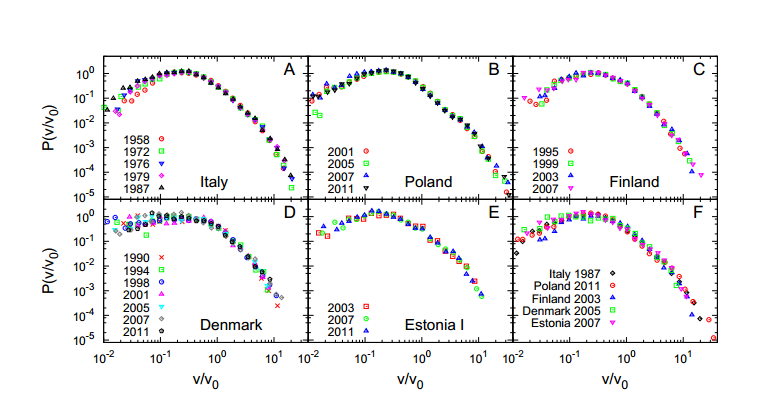

Today, Arnab Chatterjee and pals at Aalto University School of Science in Finland do just that using data from 15 countries that use the same or similar electoral systems. In general, people in these countries can vote for more than one candidate from an open list, in which one party can field more than one candidate.

The results resoundingly confirm the hypothesis. Chatterjee and co say that the (normalised) distribution of votes for candidates from a single party is the same in every country, provided they operate the same electoral rules.

“We confirm that a class of nations with similar election rules fulfill the universality claim,” they say. In fact any difference in the distribution can always be accounted for by differences in electoral rules.

Estonia is perhaps the best example, where the voting distribution switched to the universal pattern in 2002 when the electoral rules changed.

This finding is so strong that Chatterjee and co say it could be used to identify fraud, should the voting patterns not follow the predicted distribution.

It also implies that human voting patterns are remarkably predictable and based on just a few simple variables.

Just what those variables are and how they can be best targeted and influenced, are questions likely to occupy politicians, commentators and voters alike in future elections.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1212.2142: Universality In Voting Behavior: An Empirical Analysis

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.