Physicists Use Electrical Signals From Slime Mould to Make Music

Physarum polycephalum, better known as slime mould, is a single-celled creature that has attracted considerable attention in recent years for its ability to compute in unconventional ways. Various research groups have watched in barely disguised amazement as these single cells have solved mazes, recreated national motorway networks and even anticipated the timing of periodic events.

Now this extraordinary creature has added another skill to its box of tricks–the ability to make music, or at least to create sound in a controlled fashion.

Physarum grows by creating a network of protoplasmic tubes that stretch from one source of food to another. Much of this creature’s computing power comes from its ability to optimise the properties of this network.

Today, Eduardo Miranda at the University of Plymouth in the UK and a couple of pals say they’ve grown a Physarum cell in a petri dish lined with six electrodes, each topped with an oat flake to attract the protoplasmic tubes.

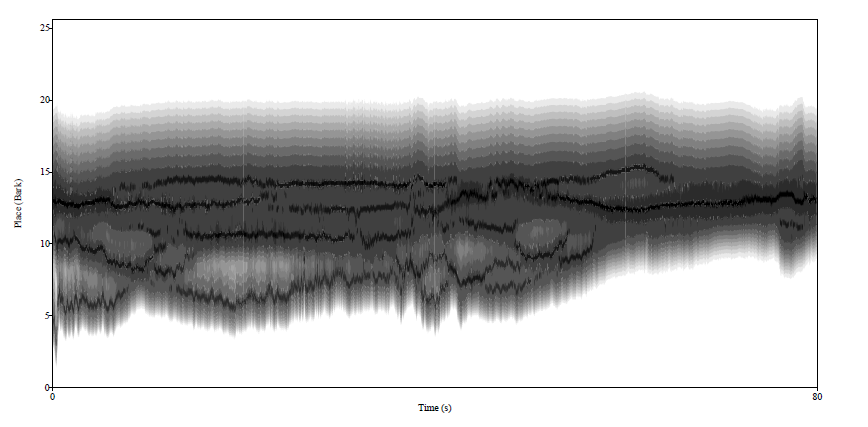

Miranda and co then measured the electrical activity at each electrode every second as the tubes grew across them, a process that took about a week to cover all the electrodes. They then plotted the results against time to compare the activity in different electrodes.

To create a sound, Miranda and co used the signal from each electrode to control the frequency of an audio oscillator. With each electrode controlling a different range of frequencies, they then added the outputs from all the oscillators to create a complex sound that represents the activity of the Physarum.

Of course, this kind of mixing is rather arbitrary but Miranda and co are mainly interested in the sound production method. They say it is possible to control the electrical activity in different parts of the network of tubes by zapping it with light.

In a sense, this allows them to “play” the Physarum like a musical instrument.

“Our own experiments…demonstrated that varying illumination gradients are good means to tune the plasmodium to produce specific oscillatory behaviours,” they say.

They go even further in abstracting this process. “The time it takes to run experiments with Physarum polycephalum can be tedious,” they complain. So instead of growing the slime mould for real, they also simulated the process on computer to speed up the process of music making, the result being a kind of Physarum synthesiser synthesiser.

That’s certainly a bizarre form of music making but Miranda has put it to good use. Earlier this year, he premiered a piece called Die Lebensfreude in Portugal that featured the Physarum electro-acoustics.

If the goal is to push music-making beyond conventional bounds, Miranda and his colleagues must surely have succeeded. Sadly, we’re unable to judge the result since there is no link in the paper or on his website to any of the resulting sound files.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1212.1203: Sounds Synthesis with Slime Mould of Physarum Polycephalum

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.