Solar Startup Silevo Scales Up, Even as Others Shut Down

The global solar panel industry is struggling—major manufacturers have posted continued losses this quarter, mainly due to a saturated market that’s left them unable to charge enough for their panels. But one startup, Fremont, California-based Silevo, is bucking the trend of plant closures and bankruptcies by planning to build a new factory next year.

Silevo says the 200-megawatt factory will let it make solar panels at costs similar to those made by solar-panel manufacturers in China, even though those manufacturers have far larger, 1,000-megawatt factories and the economies of scale that go with that.

Silevo has one key advantage—its solar panels produce significantly more power than conventional solar panels do. They generate roughly 30 percent more power than conventional ones, and hold up better at high temperatures, which could further increase their electricity production. The combination of low-cost manufacturing and high efficiency is why the company now has an order backlog of 270 megawatts, says Chris Beitel, Silevo’s vice president of business development. The company currently produces solar panels at a small 32-megawatt factory in China, and says it hopes to close financing for the new plant early next year.

In the push to make solar competitive with fossil fuels, some startups are developing novel types of solar cells that promise higher efficiencies but also require new manufacturing methods.

Silevo is taking an incremental approach, finding ways to improve conventional solar cells using manufacturing equipment already used in the solar industry, combined with equipment from other industries, such as flat-screen display manufacturing. Its founders come from Applied Materials, a large equipment supplier for the semiconductor, display, and solar industries. “We see ourselves as an evolutionary-type technology that can be put into mass production in a capital-efficient way in the near term,” Beitel says. Companies that rely on new manufacturing techniques “need a lot of time, and a lot of capital to do that.”

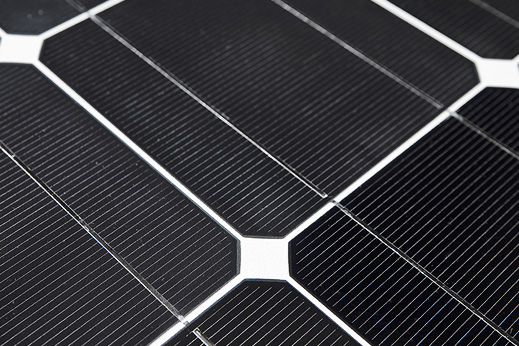

Silevo’s cells begin as silicon wafers, as in conventional solar-cell manufacturing. To those wafers, Silevo adds a layer of metal oxide, a technique borrowed from the chip industry, and a layer of amorphous silicon, something borrowed from flat-panel displays. These layers help decrease the number of electrons that get trapped within a solar cell while increasing the cell voltage, boosting the total power output. Adapting technology developed at Applied Materials, the company also replaces the silver used to collect electricity from the solar panels with copper, which is about 70 percent cheaper.

The efficiency improvements put Silevo’s solar cells in the class of high-efficiency silicon solar cells, but the company says its process is simple enough that it will compete with middle-of-the-road-efficiency solar panels on cost. Because the panels are more efficient, fewer are needed for a given system, reducing installation costs.

The company still faces a number of challenges in competing with conventional silicon-solar-panel makers. It is hard to scale up production while maintaining high-quality production at a small factory. The technology is also similar in some ways to a type of solar cell made by Sanyo that proved difficult, at first, to manufacture. “There will be similar production challenges to [Sanyo’s cells], but it looks like they’ve thought through several of the issues. Their success will likely come down to production engineering execution, as it often does for solar technology,” says Tonio Buonassisi, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

Silevo’s solar panels don’t have many years of demonstrated performance in the field, which will make banks reluctant to loan money for projects that use them. What’s more, although some experts predict that conventional solar manufacturers can’t do much more to reduce costs, costs continue to fall—so, to compete, Silevo will need to hit a moving target.

To compete with fossil fuels, Silevo will need to continue to reduce costs and improve efficiency. It hopes to bring down the price of its panels to the point that solar power will cost seven to eight cents per kilowatt-hour in sunny areas. While that’s competitive with fossil fuels in some parts of the world, in the United States, natural gas can produce electricity at just four cents per kilowatt-hour (see “King Natural Gas”).

To get to lower costs, Silevo may need to depend on more radical advances being developed by other companies, such as equipment for producing ultrathin silicon wafers to reduce materials costs and open up new ways to improve efficiency (see “Startup Aims to Cut the Cost of Solar Cells in Half” and “How to Double the Power of Solar Panels”). “Our strategy, going back to the approach of using off-the-shelf equipment, is we don’t want to be the first company to develop that, because you sink a lot of time and a lot of money into it,” Beitel says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.