The Computer That Stores and Processes Information At the Same Time

The human brain is an extraordinary computing machine. Nobody understands exactly how it works its magic but part of the trick is the ability to store and process information at the same time.

That’s entirely unlike conventional computers which store information in random access memory or on hard disc and shuttle it back and forth as required to a central processing unit.

The time and energy all this takes is the thing that ultimately limits conventional computing performance, the so-called von Neumann bottleneck. Essentially, it is this that prevents conventional computers from approaching the performance of biological ones.

All that may be about to change. Today, Max Di Ventra at the University of California, San Diego and Yuriy Pershin at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, outline an emerging form of computation called memcomputing based on the recent discovery of nanoscale electronic components that both store and process information at the same time.

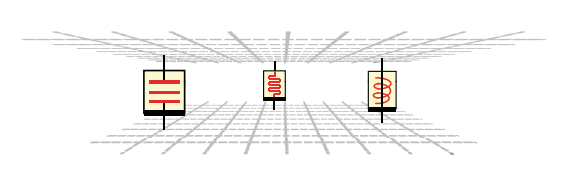

At the heart of this new form of computing are the memristor, memcapacitor and meminductor, fundamental electronic components that store information while operating as resistors, capacitors and inductors respectively.

These devices were predicted theoretically in the 1970s but only manufactured for the first time in 2008, so they are new kids on the electronics block.

Physicists immediately recognised the ability of so-called memelements to mimic biological computing and various groups have designed and built chips to exploit this idea, here for example .

But the properties of memelements that make them so good at biological computing has been hard to pin down. Which is where Di Ventra and Pershin come in. These guys have distilled the essential properties that ought to allow memelements to match the brain’s performance.

They say these properties include the ability to store information over long periods; the ability to act collectively so that the state of a memdevice as a whole depends on the states of all its memelements; a robustness against noise and small imperfections; and so on.

Perhaps the most important, however, is the ability to store and process information at the same time, a property that is entirely alien in the conventional computing world

This is an interesting approach that attempts to crystallise the best way to approach memcomputing. And it has huge potential. Memcapacitors and meminductors essentially consume no energy and so ought to allow very low energy applications. That should make it possible for them to approach the energy efficiency of natural systems for the first time.

“An important milestone in this field would be the demonstration of a memcomputing device with computing capabilities and power consumption comparable to (or better than) those of the human brain,” say Di Ventra and Pershin.

A significant factor in all this is that “mem-behaviour” is a natural property of nanoscale systems. That’s why the experimental discovery of memelements took so long after the theoretical prediction—it had to wait until physicists had developed the capability to make components this small.

And with electronic components getting ever smaller, chip manufacturers are going to have to deal with these new properties themselves as a matter of course.

That will offer all kinds of new opportunities. Biological systems, such as neurons, naturally work on this scale and so must be or have memelements. That’s not lost on Di Ventra and Perhsin: “All these features are tantalizingly similar to those encountered in the biological realm, thus offering new opportunities for biologically-inspired computation.”

An area worth watching.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1211.4487: Memcomputing: A Computing Paradigm To Store And Process Information On The Same

Physical Platform

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.