Laser-Powered Micro-Sailboats Do the Light Fandango

Flocking is a hugely spectacular phenomena, as anyone who has watched the large scale behaviour of ants or sheep or starlings or even humans can attest.

But the nature of flocking still puzzles scientists. Sure, they can reproduce the behaviour of some species in certain circumstances. But various researchers think there may be something deeper to discover here. Their search is for a grand unified theory of flocking that captures the fundamental elements of flocking behaviour.

One way to find out is to reproduce the behaviour in controlled conditions to find out which factors are important and which aren’t. That’s easier said than done with many flocking creatures.

So an alternative approach is to build autonomous robots that do the job instead. These robots must be capable of autonomous propulsion over long periods of time. They also need to be cheap and simple so that they can be produced en masse.

Today, Anrdás Búzás at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Szeged, Hungary, and a few pals show how they’ve tackled this problem with “light sailboats” each just ten micrometres in length.

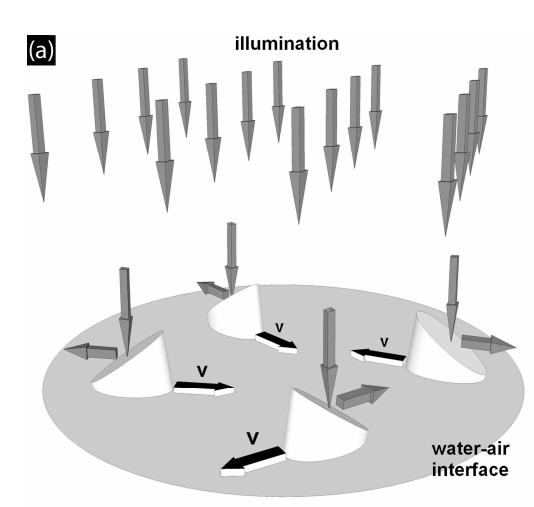

These sailboats are wedge-shaped pieces of plastic carved using photolithography and then coated with a thin layer of gold to make them more or less 100 per cent reflective. The angle of the wedge is 45 degrees to maximise the propulsion when zapped with an infrared laser.

Placed in a drop of water and illuminated from above, the sailboats zip around at speeds up to 10 micrometres per second, an order of magnitude faster than similar devices that use temperature gradients for propulsion.

So far, Búzás and co have tested the sailboats at relatively low densities so that the vehicles do not interfere with each other when they move. That has allowed the team to characterise the nature of the movement.

They say the sailboats move steadily in a single direction determined by their orientation. However, they also tend to change direction due to imperfections in the medium and in the structures themselves. On average they travel up to about 1500 micrometres before veering off course.

The plan is to use the sailboats to tease apart the fundamental properties of flocking. For that, Búzás and co will need to increase the density of sailboats to see how their mutual interactions influence flocking.

It’s still early days, of course, but a better understanding of flocking on the microscopic scale could have important implications for everything from microfluidics to drug delivery.

And if you don’t have any starlings to watch at dusk, perhaps the Hungarian sailboats might one day put on a just as spectacular show through a microscope.

Flocking is a hugely spectacular phenomena, as anyone who has watched the large scale behaviour of ants or sheep or starlings or even humans can attest.

But the nature of flocking still puzzles scientists. Sure, they can reproduce the behaviour of some species in certain circumstances. But various researchers think there may be something deeper to discover here. Their search is for a grand unified theory of flocking that captures the fundamental elements of flocking behaviour.

One way to find out is to reproduce the behaviour in controlled conditions to find out which factors are important and which aren’t. That’s easier said than done with many flocking creatures.

So an alternative approach is to build autonomous robots that do the job instead. These robots must be capable of autonomous propulsion over long periods of time. They also need to be cheap and simple so that they can be produced en masse.

Today, Anrdás Búzás at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Szeged, Hungary, and a few pals show how they’ve tackled this problem with “light sailboats” each just ten micrometres in length.

These sailboats are wedge-shaped pieces of plastic carved using photolithography and then coated with a thin layer of gold to make them more or less 100 per cent reflective. The angle of the wedge is 45 degrees to maximise the propulsion when zapped with an infrared laser.

Placed in a drop of water and illuminated from above, the sailboats zip around at speeds up to 10 micrometres per second, an order of magnitude faster than similar devices that use temperature gradients for propulsion.

So far, Búzás and co have tested the sailboats at relatively low densities so that the vehicles do not interfere with each other when they move. That has allowed the team to characterise the nature of the movement.

They say the sailboats move steadily in a single direction determined by their orientation. However, they also tend to change direction due to imperfections in the medium and in the structures themselves. On average they travel up to about 1500 micrometres before veering off course.

The plan is to use the sailboats to tease apart the fundamental properties of flocking. For that, Búzás and co will need to increase the density of sailboats to see how their mutual interactions influence flocking.

It’s still early days, of course, but a better understanding of flocking on the microscopic scale could have important implications for everything from microfluidics to drug delivery.

And if you don’t have any starlings to watch at dusk, perhaps the Hungarian sailboats might one day put on a just as spectacular show through a microscope.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1211.2653: Light Sailboats: Laser Driven Autonomous Microrobots

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.