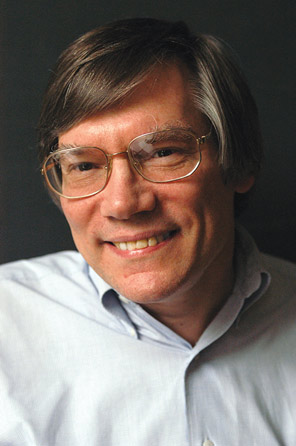

In July physics professor Alan Guth ’68, SM ’69, PhD ’72, was pleased to learn that an extra $3 million had been deposited in his bank account. Guth was one of nine physicists worldwide to find their coffers so enhanced as the inaugural winners of the Milner Foundation’s Fundamental Physics Prize.

This year’s recipients—each of whom was honored for past research achievements in physics—will form a selection committee that will choose future winners. After this year, the prize will be awarded to one or more physicists annually for what the Milner Foundation described in a statement as “transformative advances in the field.”

The Milner Foundation, founded by Russian Internet entrepreneur Yuri Milner, cited Guth “for the invention of inflationary cosmology, and for his contributions to the theory for the generation of cosmological density fluctuations arising from quantum fluctuations in the early universe, and for his ongoing work on the problem of defining probabilities in eternally inflating spacetimes.”

Guth, 65, has been a member of the MIT faculty since 1980. Much of his research has examined the application of theoretical particle physics to the early universe: What can particle physics tell us about the history of the universe? What can cosmology tell us about the fundamental laws of nature?

In 1980, he proposed that many features of our universe, including its uniformity, can be explained by a cosmological model he called “inflation”—a modification of the conventional Big Bang theory in which he posited that the expansion of the universe was propelled by a repulsive gravitational force generated by an exotic form of matter. After more than 30 years of development and scrutiny, the inflationary-universe model is now widely accepted by physicists.

One consequence of inflation is that small quantum fluctuations in the early universe can be stretched to astronomical proportions, providing the seeds for the large-scale structure of the universe; Guth and others calculated the predicted spectrum of these fluctuations in 1982. They can be seen today as ripples in the cosmic background radiation, first detected by the COBE satellite in 1992, and their properties are in excellent agreement with what the simplest models of inflation predict.

Another intriguing feature of inflation is that almost all versions of it are eternal: once inflation starts, it never stops completely. Inflation has ended in our part of the universe, but it is likely that it is continuing very far away and will continue forever. However, Guth has worked with Alex Vilenkin and Arvind Borde to show that inflation has not always been happening. To the contrary, they found that something must have preceded the era of inflation, and that some new physics—perhaps a quantum theory of creation—would be needed to understand it.

Guth has also worked on the thorny problem of how to define probabilities in an eternally inflating universe, which is difficult because any event that is possible will occur an infinite number of times.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.