Is Your Dishwasher Really Yearning for the Internet?

In the not-so-distant future, Glen Burchers believes, the gadgets in our homes—not to mention our homes themselves—will be replete with microprocessors, enabling the automation and remote control of everything from your lights to your laundry. Until this is a widespread reality, he’d like to sell you a wall outlet.

Not any old wall outlet, though. It includes an ARM processor, runs Google’s Android mobile operating system, and can connect to the Internet. This means anything you plug into it can be controlled via your smartphone, and it will also track how much power your devices are consuming.

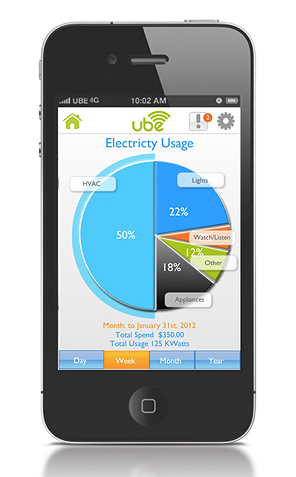

Ube, a startup Burchers cofounded in Austin, Texas, plans in the coming months to start selling the outlet along with a similarly “smart” dimmer switch and plug. It also plans to offer a free, related smartphone app that can control these and other Internet-enabled devices. For Burchers, who is also Ube’s chief marketing officer, these are the first steps toward mass availability of home automation—an idea once reserved for the wealthy, since it required customized systems to control lighting, audio, and video.

Over the past few years, enthusiasm has begun to blossom for the so-called “Internet of things,” the idea of connecting all sorts of electronics and everyday items to the Internet. Startups and established companies now offer Web-connected versions of everything from TV sets to garage door openers, as well as devices that can be used to control household appliances (see “A Startup Puts the Internet in Your Couch Cushions”). The trend has been helped along by the overwhelming popularity of smartphones, which has driven down the cost of microprocessors, sensors, and Wi-Fi chips.

The problem has been persuading consumers to buy in to the concept. According to data from the NPD Group, just 10 percent of U.S. homes included an Internet-connectable TV as of the end of June, and only 43 percent of consumers who owned such TVs were using the Internet feature for entertainment.

One problem that Ube (pronounced “you-bee”) sees is that you often need to use various smartphone apps to control different devices. In November the company plans to roll out an app—first for the iPhone, and probably for Android a month later—that will be able to control multiple Internet-connected devices produced by different manufacturers. Ube expects to start making its plug, dimmer, and outlet in March and plans to sell them for $60 to $70 apiece. The app will control devices connected to those, too.

When you open the Ube app, it hops onto your Wi-Fi network and scans for nearby Internet-enabled devices. Ube matches devices it finds with ones in its library and lets you know what it can control. Burchers says the app can control more than 200 devices, most of which are gaming systems, set-top boxes, and TVs.

In order to set up devices, keep tabs on what is located where, and allow them to work together, the app may ask a series of questions about each device. If you have a Samsung TV, for example, it might ask if your Roku box is connected to that TV.

The app will be able to interpret gestures so you don’t necessarily have to look at your smartphone. When watching TV, for instance, you swipe up or down on your phone’s screen to change channels. There will also be features allowing parents to track and control the amount of TV their children watch each week, Burchers says.

The app will be free, though Ube plans to charge users $19 per year to operate numerous gadgets interdependently (for example, turning down the living room lights when you turn on the TV). Burchers even imagines a scenario where Ube can turn off lights and lower the heat when your phone senses you’re 100 miles from home.

Creative Strategies analyst Ben Bajarin says that while home automation is “still in its infant stages,” Ube’s technology is good because it can help develop the market. Yet he says it will take something more valuable than simply being able to turn on lights for the Internet of things to succeed.

Burchers, too, believes that Ube’s first products are just the beginning. Over the next several years, he expects, the majority of new electronics will gain the ability to connect to the Web, and home builders will offer smart dimmers to new home buyers as they currently do granite countertops.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.