Muons are charged particles rather like electrons, having the same charge but over 200 times the mass. They are continuously created by cosmic rays hitting the upper atmosphere and shower the ground at the rate of about one per square centimeter per minute.

It’s easy to imagine that these muons are little more than a curiosity but in recent decades, physicists have used them for a number of interesting applications.

Because of their huge mass, muons are particularly good at penetrating dense material, like rock. In the 1960s, the American Nobel prize winning physicist, Luis Alvarez, set up muon detectors in a chamber beneath the second pyramid of Chephron in Egypt to measure the rate at which they arrived from different directions.

His idea was to use cosmic ray muons to “x-ray” the pyramid, looking for hidden chambers within the structure. By 1969, he had found no evidence of hidden chambers in the 20% of the pyramid that he’d been able to examine.

Muons are particularly deflected by heavy elements such as uranium and plutonium making it possible to spot these materials by analysing muon trajectories.. So various scientists have examined the possibility of using muons to look for hidden weapons grade plutonium and uranium in shipping containers.

The problem with this approach is that it produces a shadow gram, like an x-ray. And this limits the amount of information that can be gained about a three-dimensional object.

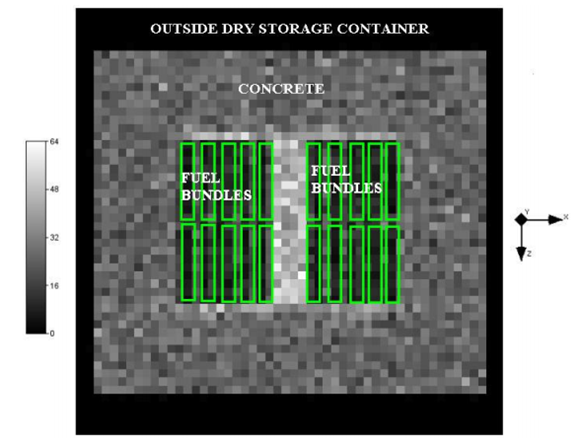

Today, Guy Jonkmans and pals at Atomic Energy of Canada Limited in Chalk River, outline a way of producing three-dimensional images from incident muons. They say this could produce detailed images of the contents of nuclear waste repositories.

Their idea is to measure the trajectory of the muons, both as they enter the repository and as they come out. That requires muon detectors both on top of the repository and underneath it.

That should reveal any muon deflected by a heavy nucleus and allow the point of deflection to be identified in three dimensions.

By building up a picture of the position of many heavy nuclei, the team can create a three-dimensional image of any structure made of heavy elements inside the repository.

Jonkman and co test their idea by simulating the passage of muons through a container of used nuclear fuel bundles and say it works well.

This could be a useful technique. One of the many ongoing problems facing the nuclear industry is that of characterising the waste left over from earlier eras.

Nobody knows what fills many of the waste storage tanks in places such as the Hanford Site in Washington state, because records were lost or not kept in the first place. And determining the content of these repositories using conventional methods are simply too dangerous.

The next step, of course, is to put the idea into practice. That will require some detectors, some nuclear waste and a significant amount of experience in dealing with both. A task that’s not going to be quick, easy or cheap.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1210.1858: Nuclear Waste Imaging and Spent Fuel Verification by Muon Tomography

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.