Cyborg Tissue Monitors Cells

Researchers at Harvard University have constructed a material that merges nanoscale electronics with biological tissues—a literal mesh of transistors and cells.

The cyborg-like tissue, described online at Nature Materials, supports cell growth while simultaneously monitoring the activities of those cells. It could improve in vitro drug screening by allowing researchers to track how cells in a three-dimensional environment respond to drugs in real time, the authors say. It may also be a first step toward prosthetics that communicate directly with the nervous system, and tissue implants that sense and respond to injury or disease.

Previously, to probe electrical activity of living systems, scientists have developed flat, flexible devices that stretch along the outside of an organ, such as the heart, brain, or skin (see “Making Stretchable Electronics”). But these materials only monitor electrical activity at the surface of a tissue.

The new scaffolding was made by a team of researchers that includes Bozhi Tian, a 2012 member of Technology Review’s TR35 (see “35 Innovators Under 35: Bozhi Tian”); Harvard University chemist Charles Lieber; Daniel Kohane, director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children’s Hospital; and Robert Langer, a chemical engineer and Institute Professor at MIT. The group set out to design a three-dimensional scaffold that integrates electronics directly into living tissues.

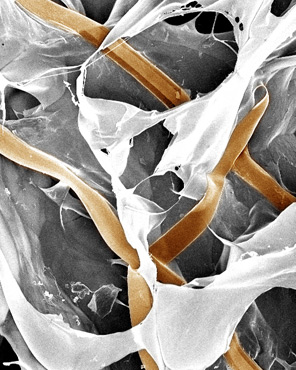

The nanoelectronic scaffolds were made from a thin mesh of metal nanowires, either straight or kinked, dotted with tiny transistors that detect electrical activity. The researchers folded or rolled the mesh into a three-dimensional structure to simulate a piece of tissue or a blood vessel, respectively. The result is a scaffold that is both porous and flexible—not an easy feat for electronics. “These scaffolds are mechanically the softest electronic materials that have ever been made,” says Lieber.

The scaffold was then seeded with cells or merged with conventional biomaterials, such as collagen, into hybrid scaffolds. “It shows, from a materials perspective, that you can combine these electronic networks with virtually anything,” adds Lieber.

To test the construct’s sensing capabilities, the team performed experiments with living cells. They grew neurons in the scaffold, then successfully monitored the cells’ firing activity in response to excitatory neurotransmitters; they observed heart cells on one side of the tissue beating in subtly different ways than cells on the other side; and they monitored pH changes on the inside and outside of a simplified blood vessel, made of rolled construct and smooth muscle cells.

Lieber says numerous pharmaceutical companies have already expressed interest in the scaffolds to monitor drug responses in different tissues. “That’s the nearest-term application,” he says—but not the ultimate goal. Someday, Lieber would like to develop tissue grafts that can report their function to doctors and provide immediate feedback to a tissue when necessary, such as releasing a drug into the skin or lungs. “We have the opportunity to merge electronics with cellular systems,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.