Getting a shot at the doctor’s office may become much less painful in the not-too-distant future.

MIT researchers have engineered a device that delivers a tiny, high-pressure jet of medicine through the skin without the use of a hypodermic needle. The device can be programmed to deliver a range of doses to various depths—an improvement over similar jet-injection systems that are now commercially available.

Among other benefits, the technology may help reduce the potential for needle-stick injuries and help improve compliance among patients who must regularly inject themselves with drugs such as insulin.

“If you are afraid of needles and have to frequently self-inject, compliance can be an issue,” says Catherine Hogan, a research scientist in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and a member of the research team. “We think this kind of technology … gets around some of the phobias that people may have about needles.” The team published its results in the journal Medical Engineering & Physics.

Jet injectors, which produce a high-velocity jet of drug that penetrates the skin, are among several new technologies that researchers have developed to deliver protein-based drugs whose molecules are too large to pass through the pores from conventional transdermal patches. But the mechanisms used by existing jet injectors, particularly those with spring-loaded designs, eject the same amount of medication to the same depth every time.

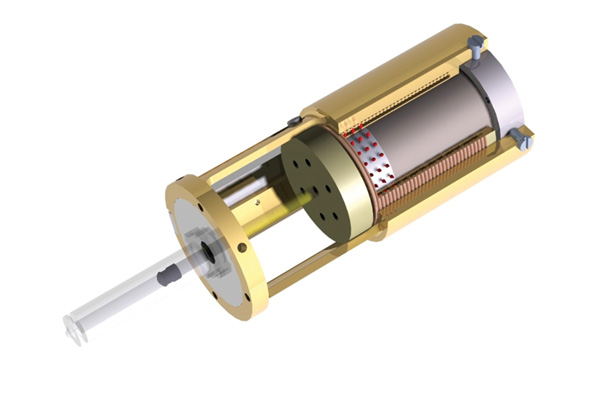

The system developed by the MIT team, led by mechanical-engineering professor Ian Hunter, is built around a mechanism called a Lorentz-force actuator—a small, powerful magnet surrounded by a coil of wire that’s attached to a piston inside a drug ampoule with a nozzle no wider than a mosquito’s proboscis. When current is applied, it interacts with the magnetic field to produce a force that pushes the piston forward, ejecting the drug through the nozzle at very high pressure and velocity (almost the speed of sound in air). The speed of the coil and the velocity imparted to the drug can be controlled by the amount of current applied.

“If I’m breaching a baby’s skin to deliver a vaccine, I won’t need as much pressure as I would need to breach my skin,” Hogan says. “We can tailor the pressure profile to be able to do that, and that’s the beauty of this device.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.