Startup Has Language Learners Translating the Web

Luis von Ahn is frustrated with the Internet. More specifically, with the amount of content that is available only in English—which is to say, most of it. “The Web in Spanish is just shittier,” he says, his voice tinged with a Spanish accent.

So von Ahn, an associate professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University who grew up in Guatemala, is doing something about it.

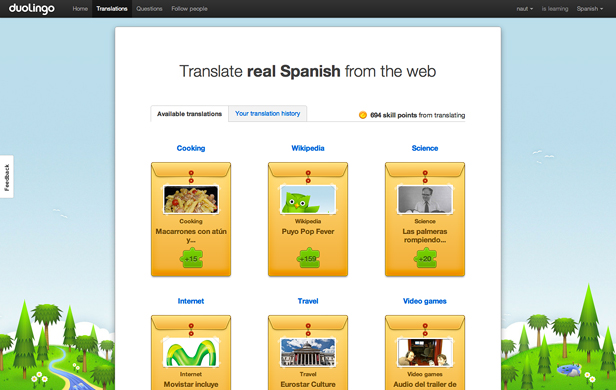

Late last year, he and cofounder Severin Hacker, who was previously a student of his at CMU, launched Duolingo, a startup that combines language learning with crowdsourced translation. As users gain the knowledge of a new tongue, they help translate documents on the Web for others. Ultimately, he hopes Duolingo’s efforts will translate the Web into every major language.

After spending months in a private beta testing phase, the site opened up to all comers late this month, offering free online English lessons for Spanish speakers and lessons in Spanish, German, and French for English speakers. Other languages, such as Mandarin and Portuguese, are expected to be added later this year.

The territory isn’t entirely new to von Ahn. In 2000, he helped develop the Captcha—the test that websites use to distinguish humans from spam-spewing robots by asking them to reënter blurred or distorted strings of letters and numbers. After that, von Ahn created reCaptcha, a system that harnesses Captcha tests to digitize the text of old printed books.

Von Ahn began planning to translate the Web several years ago, and he thought it made the most sense to have humans complete the task, since existing machine translation technologies like Google Translate are far from perfect. But he needed a way to motivate people to participate. Teaching users a new language by getting them to translate sentences from that language into English could keep them engaged, he thought.

The setup seems to be working. Duolingo emerged from its private beta this week with over 125,000 active users who have so far translated 75 million sentences from Wikipedia and other online sources. Soon the site will allow people to upload their own documents for translation, von Ahn says. “We’re translating millions of sentences a day already, which is a pretty good scale,” he says.

Duolingo can help novices gain intermediate language skills, von Ahn says—a level some have achieved by spending about 100 hours using the site. But users learn the most in the first five hours, he says, and that is usually enough to enable them to get around in a country where the language is spoken.

If the site can snag a million active users, von Ahn thinks, Duolingo could make a “good dent” in translating online texts. The goal could be difficult to achieve, though, since about half the people who start using the site end up quitting. Von Ahn likens it to joining a gym: everyone wants to do it, but many give up when they find out how hard it is.

When you sign up to flex your language-learning muscles, Duolingo determines how well you already know your chosen language and then presents sentences to translate, geared to your skill level. There are a number of activities to keep users learning, such as listening to a voice speak a sentence and parroting it back aloud (I tried this in the office and found myself embarrassedly yelling at the computer in French). When Duolingo shows you a new word, you can click on it to see the definition. The site then asks you to put it into the proper context in a sentence.

To illustrate how well Duolingo’s approach works for translating online text, von Ahn sent over a Spanish translation of part of a story in the New York Times about Anders Behring Breivik, who admitted to killing 77 people in a rampage in Norway last summer. The Duolingo version was marred only by a missing accent mark over an “e,” while a Google Translate version was much more difficult to comprehend.

Chris Callison-Burch, an associate research professor of computer science at Johns Hopkins University whose work includes statistical machine translation and crowdsourced translations, calls Duolingo’s approach “really exciting.” Beyond helping people learn and providing translations of online content, the data Duolingo produces could be used to help improve machine translation, he says.

Von Ahn says Duolingo does plan to do this, and he believes that at some point machine translation will almost certainly match the power of human translators. Still, as he points out, we aren’t there yet, and people have been working on the problem for decades. “Who knows how long it’s going to take?” he asks.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.