New observations from a spacecraft orbiting Mercury have revealed that the planet harbors a highly unusual interior—and the craft’s glimpse of Mercury’s surface suggests a very dynamic past.

The observations were taken by a probe called Messenger (short for Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging), the first ever to orbit the tiny, pockmarked planet.

Getting into orbit about Mercury was no easy feat, mostly because of its proximity to the sun. Any spacecraft heading toward the planet speeds up, drawn in by the sun’s powerful gravitational field. To counteract the sun’s pull, an operations team programmed the probe to fly around Venus twice, and Mercury three times, before slowing down enough to be captured in Mercury’s orbit.

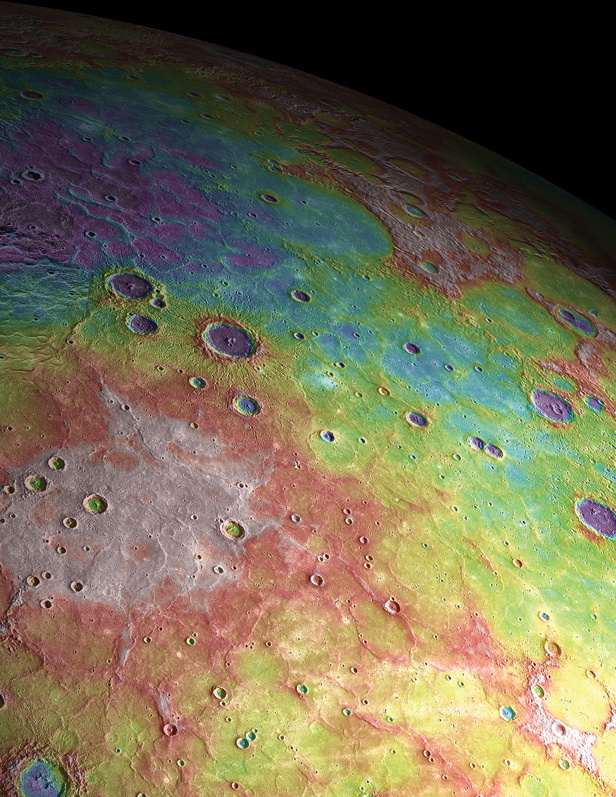

Once in Mercury’s orbit, the probe used laser altimetry to measure the planet’s surface elevations (shown here) and used radio tracking to record its gravitational field. MIT researchers were part of a team that created precise maps by analyzing the data.

From the gravity estimates, the research team found that Mercury probably has an exceptionally large iron core making up approximately 85 percent of the planet’s radius. (Earth’s core, by comparison, is about half the planet’s radius.) This means that Mercury’s mantle and crust occupy only the outer 15 percent or so of the planet—they’re proportionally about as thin as the peel on an orange.

The team, which reported its results in Science, also mapped out a large number of craters on the planet’s surface, making a surprising finding: many of them have tilted over time, suggesting that processes within the planet deformed the terrain after the craters formed.

“Prior to Messenger’s comprehensive observations, many scientists believed that Mercury was much like the moon—that it cooled off very early in solar system history and has been a dead planet throughout most of its evolution,” says coauthor Maria Zuber, a professor of geophysics. “Now we’re finding compelling evidence for unusual dynamics within the planet, indicating that Mercury was apparently active for a long time.”

The scientific process that led to the team’s results was a journey in itself, says coauthor Dave Smith, a research scientist in Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences. “We had an idea of the internal structure of Mercury, [but] the initial observations did not fit the theory, so we doubted the observations,” he says. “We did more work and concluded the observations were correct, and then reworked the theory for the interior of Mercury that fit the observations. This is how science is supposed to work, and it’s a nice result.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.