Marketers Try to Master Facebook’s Feed

Climbing to the top of Google’s search results—by tweaking the structure and contents of a Web page—is the basis for the multibillion dollar industry known as search-engine optimization. It’s an industry that has boomed over the last decade because businesses of all sizes can gain and lose a fortune depending on where their Web pages rank. Scammers also came in droves, seeking to trick Google’s algorithms into showing pages hawking their unsavory wares when searchers enter common queries.

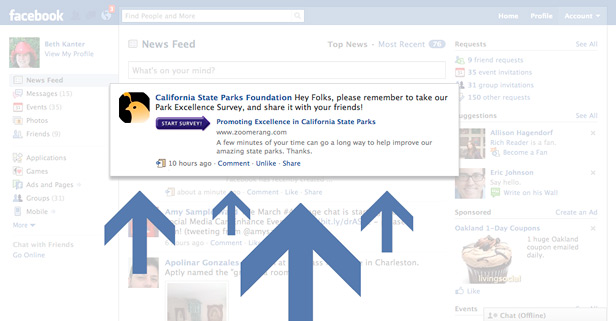

The rise of Facebook as a destination of businesses as well as people poses a new problem for tech-savvy marketers. Many companies have attracted thousands or even millions of “fans” to their Facebook page, but because Facebook filters the posts that people see in their news feed—using its own mysterious algorithm—those companies aren’t reaching many of their Facebook fans with updates.

This could also be the basis for a new growth industry. “News feed optimization is still at its early stages. I’d compare it to search in 2001,” says Tim Chae, founder of PostRocket, a startup that connects with Facebook pages, analyzes their metrics, and spits back daily posting suggestions to its owners. The company raised $610,000 in seed funding this month. The social media marketing company Buddy Media, which works only partly on these problems, sold to Salesforce recently for $699 million.

The social network’s news feed sorting filter is called EdgeRank. It helps Facebook keep users updated on friends’ activity without overwhelming them with every single post, “like,” and comment spilling out of their social graph.

It’s unclear when EdgeRank came into use, but a defining moment happened in 2010, when the company first provided public details on how it curates users’ news feeds.

The details are few, but what’s known is that the EdgeRank formula is based on how Facebook judges the closeness of two people (or a person and a brand), how valuable an activity is (sharing a photo is better than clicking “like,” for instance), and how long ago it took place. Precisely how these factors are measured is not revealed, and, like Google, Facebook is constantly making tweaks.

The algorithm is becoming important to marketers, who face pressure to justify the budgets being poured into Facebook. PageLever, a Facebook analytics company started in 2010, estimates that the average company page reaches fewer than 8 percent of its fans with updates. That could get worse, as more people post more content from smart phones, thereby cluttering feeds.

Zachary Welch, an expert at “news feed optimization theory and strategy” with the agency Brand Glue, says the highest figure he’s seen for a company’s posts reaching its Facebook fans is 39 percent, but most companies might top out in the low 20s.

Chat Wittman quit his job in social media marketing last year to found EdgeRank Checker, a company that offers a score of Facebook pages based on how posts are performing with EdgeRank. “This is the future of Facebook marketing, understanding that algorithm. I dedicated myself to learning it and testing it,” he says.

As with mastering search-engine optimization, cracking EdgeRank is part science and part finesse. So far, Wittman has signed up 200,000 pages to his service. Fortune 500 companies, including Walgreens, are clients, he says. He says he is reverse-engineering the algorithm by analyzing the inputs (posts from pages) and outputs (Facebook’s metrics about who sees those posts). “What I was able to do is figure out what was happening inside that black box.”

Despite the fancy math, most agree what matters is the obvious: posting content people are interested in. And, as with the search industry, there are already swindlers and bad actors trying to exploit the system, sometimes trying to boost a page’s clout with fake fans. There’s no oversight force, and many false or poorly researched claims are made and spread, says Wittman.

Facebook does not directly benefit from much of this activity, yet. Eventually though, businesses, and maybe even people, might pay Facebook to make sure their posts rise to the top. In fact, Facebook, which is seeking to expand its advertising dollars, recently introduced “Reach Generator” so that companies can pay to reach more of their fans. It is also reportedly testing a “pay to promote” system directed at average people.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.