Google Wave’s Inventors Give Gmail a Facelift

In 2009 Google launched a collaboration site called Wave to show the world “what e-mail would look like if it were invented today.” In 2010, after a lukewarm response, the company killed it off for good.

Now three leading people from the failed but iconic project, all of whom left Google in 2011, are making another attempt to “fix” e-mail. They recently began sending out invites to Fluent, a site that promises an alternative interface to operate a Gmail account. The service connects to Gmail using the application programming interface (API) that Google provides to allow other software to tap into its service.

Access to the service is slowly being dripped out to people that signed up since the team announced Fluent early this year (an interactive demo on the site shows how Fluent works). When your place in line does come up, an e-mail invites you to click through to the site, which then asks for permission to access your Gmail account. After Fluent has had time to sort through your messages, you can start playing in your new inbox.

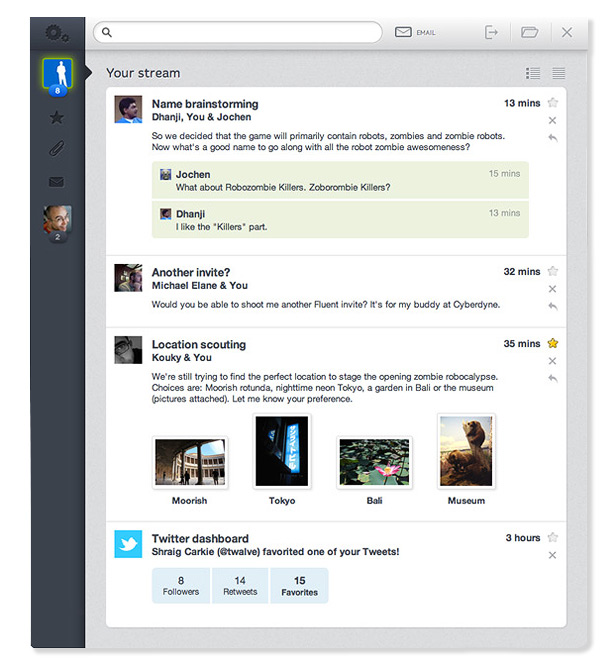

At first, it feels a bit like Twitter. All e-mail users are familiar with the classic message list showing just names and subject lines, sometimes accompanied by a reading pane and always surrounded by a profusion of detailed buttons and menus. Fluent drastically simplifies all that, combining the message list and viewing pane into one Twitter-style “stream.” Each box in that stream shows the sender, subject, and the content of an e-mail and presents a small text box for you to type a reply. That’s pretty much it. Off to the side are a small number of extra buttons for functions like viewing different e-mail folders, but they are shaded out to keep you focused on that stream.

Using Fluent is mainly a matter of interacting with that never-ending chain of messages. If you try to scroll to the bottom of the page, Fluent loads up new items without noticeable delay. A handful of buttons on the top of each item let you do things like delete or archive a message with a single click, and when you do so, the stream smoothly slides up to fill the gap. To reply to a message, you click once in a small box underneath and start typing. I didn’t time it, but dealing with e-mail this way feels faster and more efficient in terms of clicks and mouse movements than using a conventional e-mail program. The design is a great fit on a tablet (I tried it on an iPad).

Fluent was built by Cameron Adams, lead designer on Google Wave, Dhanji Prasanna, who worked on Wave’s search function, and Jochen Bekmann, that project’s tech lead. But the features that most defined Wave are largely conspicuous by their absence from Fluent. Whereas Google Wave hooked those that liked it by being built up and rich in features, the trio’s new project feels well-designed by dint of being stripped down. Wave was a bit like a chronometer watch that exposes some of its oh-so-clever workings. You could sense the code at work when you saw a message reform itself in real time as a distant person typed and made edits. Fluent is surely not built with beginner’s code, but the software engineering skill is hidden behind a plain, well-focused exterior. The flashiest thing is the “instant” search, which finds results as you type like Google Instant—the Web search results that appear as you type a query into Google. The same functionality is not available with Gmail.

That’s not to say that Fluent is purely a nice interface. It also steers a user to use e-mail differently, and that has echoes of Wave. One goal of that project was to make online communication more like collaborating with a person around a table in real life. Fluent has a similar effect by making threads of replies to a message feel more interactive and chatty. There is very little in between the content of a message and the replies below, which look something like comments on a Facebook update. I liked that, and think it led to my replying more promptly to some messages by lowering the perceived barrier to composing a message.

Making e-mail more casual is not without drawbacks, though. One conceptual problem for this writer was the tension between the fact that Facebook and Twitter streams are ephemeral, and you are not supposed to read every update, and e-mail is not. People take e-mails much more seriously than they do social media posts, despite the way Fluent looks. Making the default behavior of the reply box to be “reply all” adds to that potential culture clash.

Fluent has received other good reviews, and a search of Twitter comments turned up no gripes. But the current waitlist for the beta is over two months. Anyone wanting to try a new look Gmail right away might instead look to Zeromail, a service from another Australian startup. It’s less visually appealing than Fluent but also shows e-mail as a stream and adds novel features of its own. Most impressive is an ability to automatically put “notification” e-mails, such as sent by Twitter or Facebook, and “newsletters,” like Groupon, into separate, dedicated categories. That leaves the main inbox looking much more human.

That such a facelift of Gmail feels necessary is an indication of just how much things have changed since Google launched the service in 2004. Gmail instantly outmoded all other Web-based e-mail, and arguably still leads in terms of features and user experience. But the way we use the Web to communicate has changed significantly since 2004. Fluent and Zeromail are nice attempts to bring e-mail in line with that, but ultimately the thought behind Google Wave may still be right: e-mail is an anachronism.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.