New Cement-Making Method Could Slash Carbon Emissions

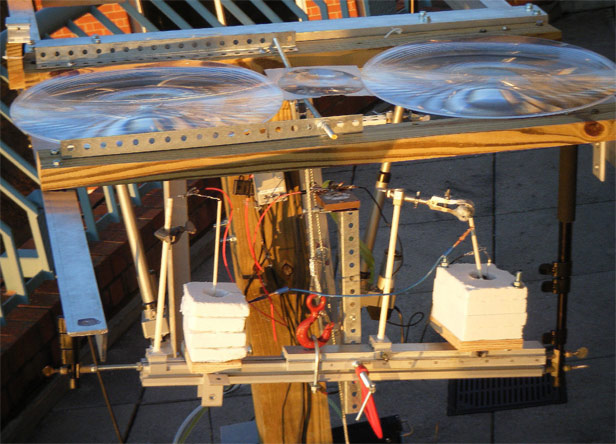

Researchers at George Washington University have bolted together an ungainly contraption that they say efficiently uses the energy in sunlight to power a novel chemical process to make lime, the key ingredient in cement, without emitting carbon dioxide. The device puts to work about half of the energy in sunlight (solar panels, in comparison, convert just 15 percent of the energy in sunlight into electricity).

Cement production alone emits 5 to 6 percent of total man-made greenhouse gases, and most of that comes from producing lime. Some of the greenhouse-gas emissions from conventional cement production come from using fossil fuels to heat up limestone to high temperatures—about 1,500 ⁰C. Replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy is straightforward, but not necessarily economical. The new work focuses on a harder problem. About 60 percent of the carbon-dioxide emissions from cement production is inherent to the process. Lime is made by heating up limestone—that is, calcium carbonate—until it releases carbon dioxide.

The new process changes the chemistry. Rather than emitting carbon dioxide, it converts the gas, using a combination of heat and electrolysis to produce oxygen and either carbon or carbon monoxide, depending on the temperatures employed. Both carbon and carbon monoxide are useful products that might otherwise have been made using fossil fuels.

To make the electrolysis practical, the researchers mixed solid calcium carbonate with liquid lithium carbonate, which is molten at the temperatures that are optimal for the process—about 900 ⁰C. The liquid form is conducive to electrolysis. The elevated temperatures lower the amount of electricity needed to electrolyze, and cause the lime to precipitate out of the mixture, making it easy to collect. (At lower temperatures, the lime is more soluble, so it doesn’t precipitate.)

To demonstrate the process, the researchers built a device that includes three Fresnel lenses for concentrating sunlight. Two of those heat up the mixture of lithium carbonate and limestone. Those are the largest lenses. Their relative size reflects the fact that most of the energy needed for the process goes to heating up the mixture. The third, smaller lens focuses light on a high-efficiency solar cell, which provides the relatively small amount of electricity needed to electrolyze the hot carbonate mixture.

The device is just a proof of concept, not ready for commercialization. It’s small, and it works only when it’s sunny—and intermittent operation isn’t ideal for an industrial process. The researchers propose using molten salt to store heat, a system used in some solar thermal power plants. That would allow the process to run day and night. The electricity could come from using the heat to generate steam to spin a turbine, as in a solar thermal power plant, or from any other source of electricity.

Stuart Licht, the professor of chemistry at George Washington University who led the work, estimates that the process, if it can be scaled up, could be cheaper than conventional lime production. He says it’s more efficient than solar panels because it uses parts of the solar spectrum that solar cells can’t efficiently convert into electricity.

The process still requires a lot of energy, says C12 Energy CEO Kurt House, who has developed low-carbon concrete production processes. “It comes down to how you want to use solar energy,” he says. “If the efficiency is as good as they say it is, then I agree, this is very, very interesting. But I’m skeptical.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.