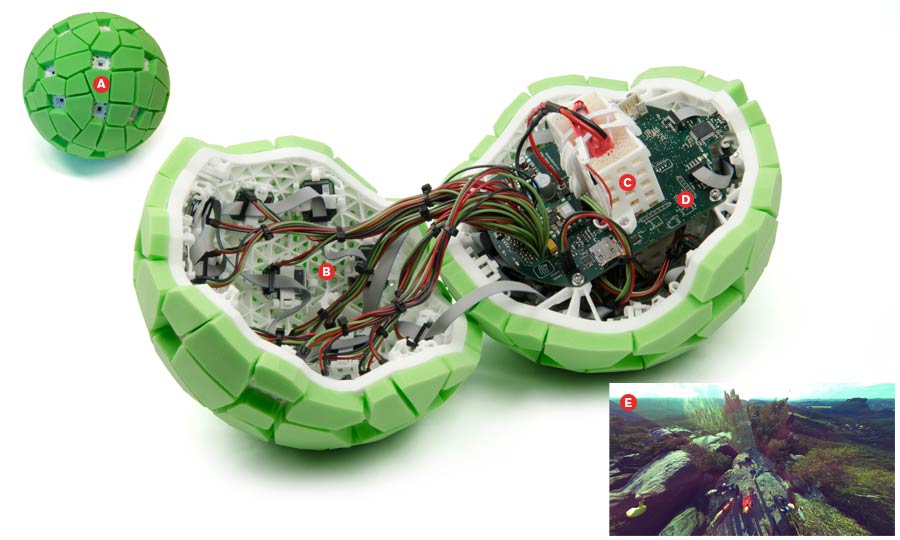

Eye Ball

If you toss this foam-covered ball skyward, an accelerometer inside determines when it has reached its maximum height. At that moment, 36 cameras are triggered simultaneously, creating a mosaic that can be downloaded and viewed on a computer as one spherical panoramic image. The ball was created by researchers at the Technische Universität Berlin after one of them, Jonas Pfeil, labored to create panoramas while on vacation in Tonga. On that trip, he tried a cumbersome process that required snapping pictures in different directions and stitching them together later in a photo-editing program. Now he hopes to license the camera-ball technology for commercial production.

A. Outer Shell

The sphere, about the size of a softball, is protected by blocks of foam. Thirty-six cell-phone camera modules, each with a resolution of two megapixels, are set into the surface. Each module stores its portion of the mosaic until it is transferred to the ball’s microcontroller.

B. Inner Shell

See a demo of the ball camera in action here.

The prototype’s inner shell, made from a strong yet somewhat flexible nylon material, gives the ball structural strength. The shell was made using a 3-D printing service.

C. Power Source

The ball’s power source, a relatively heavy lithium-polymer battery, is secured in an inner cage to keep its center of gravity close to its geometric center so that it behaves predictably when thrown.

D. Microcontroller

A microcontroller uses data from an accelerometer to determine when to trigger the cameras. Then it stores the resulting mosaic of images. The prototype can store one mosaic, but it has a hardware slot for a memory card that could store additional panoramas.

E. Panorama

Images are uploaded to a personal computer via a USB connection. Software on the computer allows panoramas to be rotated or enlarged, and portions can be exported as 2-D images.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.