First Demonstration of Inkjet-Printed Graphene Electronics

Inkjet technology has been a revolution. First, there is digital image printing, which has become faster and more flexible than anybody imagined (although not necessarily cheaper).

Then came 3D printing in which one layer of material is printed on top of another to build up a three dimensional objects. That’s become a standard way to make complex prototypes while others are using it to ‘print’ different kinds of chocolates, creams and icings.

Then there are the groups who have added conducting polymers to the inks and used them to print circuits onto flexible substrates. These are being used to make everything from digital paper to disposable RFID tags. And they can be printed onto sheets of essentially any size, unlike conventional high performance circuitry which must be forged in exotic conditions inside multibillion dollar fabrication plants .

There is a problem however. Inkjet printed electronics underperform conventional integrated circuitry by a significant margin–printed thin film transistors are simply bigger and slower than silicon-based models. So the race is on to improve their performance.

Today, Andrea Ferrari and buddies at the University of Cambridge in the UK show off a significant step forward. These guys have found a way to replace or augment the conducting polymers in these inks with graphene, the wonder-material of the moment.

It’s not hard to see why. The electronic properties of graphene are hard to match and make it idea for nanoelectronics. But the difficulty is combining it into an ink that readily forms small droplets–something that is obviously essential for inkjet printing.

This is essentially the breakthrough that Ferrari and co have achieved. They’ve found a way to readily produced graphene by chemically chipping flakes off a block of graphite and filtering them to remove any that might clog the printer heads.

They then add the flakes to a solvent called N-Methylpyrrolidone, or NMP, which minimises problems such as the coffee ring effect that can occur when some solvents evaporate.

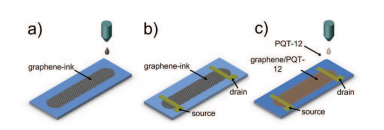

Finally they’ve put this stuff in their printers and printed out a few circuits and thin film transisters.

The results are promising. The graphene-based inks match or beat the performance of most other inks available today. That’s pretty good for a first attempt since improvements will certainly follow.

“This paves the way to all-printed, flexible and transparent graphene devices on arbitrary substrates.,” say Ferrari and co in concluding their paper. Which means we can expect to see much more on this in the coming months and years.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1111.4970: Ink-Jet Printed Graphene Electronics

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.