Going Offline

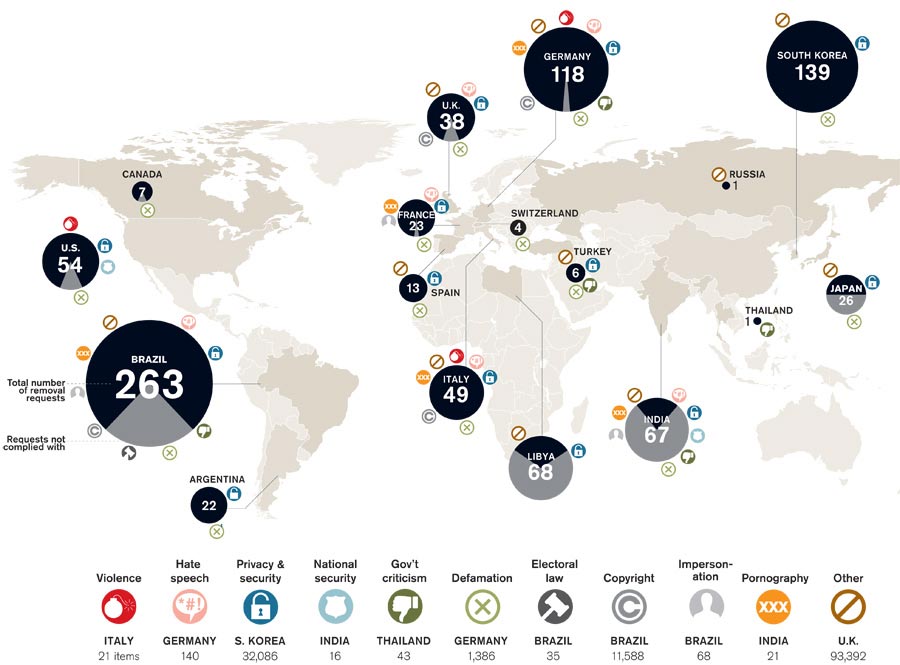

British officials got upset about 93,000 online ads that led unsuspecting people to a Web page for a phony government agency. Thai leaders registered a complaint about 43 YouTube videos that mocked or criticized their king. Argentine courts objected to defamatory material about people that appeared in Web searches.

Such are the insights revealed by Google’s Transparency Report. It’s a detailed accounting of how many times governments have asked the company to remove content or block it from being seen in their countries. Here we’ve plotted data from the most recent report, covering the last half of 2010. It breaks out takedown requests by country (in black), the reasons, and the number of requests rejected (in gray). Note that one request can cover multiple items. Google will decline requests for being too broad or vague; it also appears more likely to comply with a court order than a plea from a government agency.

Brazil is the top requester because Google’s social network Orkut is so popular there. At the other end of the spectrum, China made no requests. Since Google stopped censoring information for Beijing in the first half of 2010, China has used its “Great Firewall” to block things itself.

Information graphic by Mike Orcutt and Tommy McCall

Notes: The governments of Australia, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Greece, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam also asked for content to be taken down but are not shown here because they fell below a threshold Google uses when it publishes details—they made fewer than 10 requests and sought the removal of fewer than 10 items. Another section of the Transparency Report, which reveals how many times governments sought data about individuals, is available at google.com/transparencyreport.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.