Genome of the Black Death Revealed

For the first time, scientists have reconstructed the genome of an ancient pathogen: the bacterium that caused the Black Death, or bubonic plague. This plague killed approximately 50 million people between 1347 and 1351, about half the European population. Similar strains still circulate today, but with much less devastation, killing about 2,000 people per year.

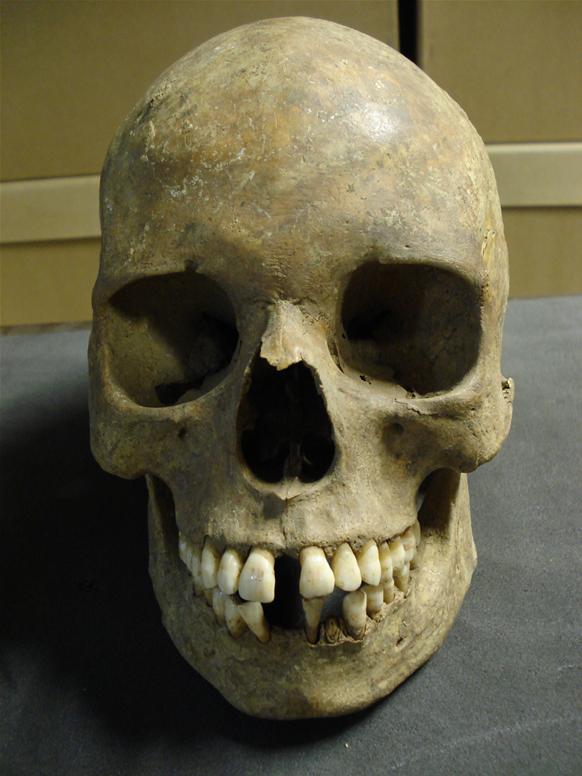

Researchers pulled DNA fragments of the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which causes the plague, from remains buried in the East Smithfield “plague pits” in London. They had previously developed a way to distinguish ancient DNA from modern DNA; one of the challenges in analyzing ancient DNA is getting rid of contamination from modern organisms. They then sequenced that DNA, reading about 99 percent of the genome, and compared it to modern strains.

Surprisingly, “we do not see single position in this ancient genome that cannot be found in modern strains,” said Johannes Krause, a researcher at the University of Tübingen, Germany, in a press conference.

Researchers say it’s not yet clear why this ancient version was so deadly or why the modern versions, which are genetically highly similar, are less virulent. “There is no particular smoking gun,” said Hendrik Poinar, a geneticist at McMaster University, at the press conference. The research was published online today in the journal Nature.

The devastation of the Black Death may have been due to the climate at the time—a rapid onset of cold, wet weather—and the onset of a new bacterium in an immune-challenged population. Scientists are also exploring the possibility that the original plague put evolutionary pressure on humans, leaving behind those with better innate immunity.

But it may be that the particular combination of genetic factors in the ancient strain was more deadly. While each individual genetic change can be found in modern strains, the specific constellation of genetic factors in the genetic strain has not.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.