Will Super Wi-Fi Live Up To Its Name?

It’s likely that a few years from now, Americans’ laptops, smart phones, and other wireless devices will be able to get online using “Super Wi-Fi,” a new standard that will increase capacity in places where regular Wi-Fi networks have become overcrowded. The bad news: most people won’t be able to use those airwaves to make long-range connections, which was supposed to be the major technological advance that would put the “super” in Super Wi-Fi.

A new model for managing America’s airwaves was unveiled Monday, as part of a plan by Federal Communications Commission chairman Julius Genachowski to ease what he calls America’s “spectrum crisis.” As wireless devices proliferate, Genachowski has repeatedly said, the U.S. needs to free up more spectrum for modern uses.

Right now a giant swath of America’s best airwaves is used mainly by local TV stations. The band is almost 300 megahertz wide—slightly more raw capacity than AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint have, combined. The idea of Super Wi-Fi is to make use of the vacant airwaves that lie between existing TV stations’ frequencies, gaps known as white spaces. However, other applications, such as wireless microphones, already have some rights to those frequencies. That is where an FCC-approved database, which was opened Monday for public testing, comes in. It will allow someone who, for example, wants to use a wireless microphone for a musical in Reno, Nevada, to register where he needs to use those airwaves. New Super Wi-Fi devices can access that database and make sure not to send out interfering signals. If he doesn’t register, he can’t be assured of having that spectrum free.

The new system is a significant advance over the old way of governing the nation’s airwaves, says Jeff Schmidt, the director of engineering at Spectrum Bridge, which is overseeing the first white-space database. Right now large parts of the spectrum go to waste because the license holder who controls them has no incentive to let other people use them, even when it doesn’t need them. “The old system was that [a company] got a chunk of spectrum and used it for its network,” says Schmidt. “White spaces allow a bunch of dissimilar users to share spectrum efficiently.”

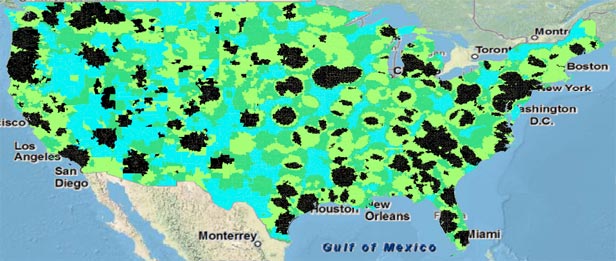

The problem, as the database shows, is that the places where spectrum is in the shortest supply—cities where lots of people must share the same airwaves—are also the places with the most TV channels and thus the least available white space.

Under government rules designed to protect local TV stations from harmful interference, high-power Super Wi-Fi signals (up to 4 watts), which can travel for miles, must give TV channels a wide berth. Low-power Super Wi-Fi signals (less than 40 milliwatts) face fewer restrictions.

The result is that while there are 48 channels potentially available for long-range Super Wi-Fi, zero or one channel will be available for long-range use in the places most Americans live—so Super Wi-Fi networks significantly bigger than today’s home Wi-Fi networks won’t be practical. In rural areas, the longer-range systems could prove a boon, although even there, most of the spectrum will still be off-limits.

The short-range devices will supplement existing Wi-Fi systems, which can sometimes run out of capacity when lots of people in one vicinity try to use them. Super Wi-Fi will benefit from using lower-frequency waves that travel farther and penetrate walls more easily, but those advantages will be reduced, if not completely offset, by the 40 milliwatt power limit. (Regular Wi-Fi can use up to 1 watt of power.)

Ultimately, Congress could decide to loosen the limits on Super Wi-Fi—over the objections of TV broadcasters. According to the broadcasting industry, not even current limitations are stringent enough, which is why it has been fighting to block the white-space rules.

Should Congress decide that Super Wi-Fi is a better use for the nation’s airwaves than local UHF TV stations, another upside of the new database is that it would be easy to crank up the power of Super Wi-Fi. Says Schmidt, of Spectrum Bridge, “They change the policy, we change a line of code—and voilà.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.