Back in 1999, a computer scientist at Cornell University began monitoring the way that the Windows NT 4.0 operating system used files. What he found was astonishing.

About 80 per cent of all files that NT creates are either over-written or deleted within 5 seconds of being born.

Today, Ragib Hasan and Randal Burns at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore say this ought to give programmers pause for thought. Deleting data requires energy, which means that a substantial fraction of a computer system’s energy budget is currently devoted to creating and then almost immediately scrubbing data.

And if the wasted energy weren’t bad enough, computer memory has a limited life span. Flash memory, for example, has a lifespan of 100,000 cycles. So cycling it needlessly brings the inevitable breakdown closer

Surely, there’s a better way, say Hasan and Burns.

As it turns out, waste management is a maturing discipline, at least as far as physical waste is concerned. Why not use the same ideas in the data industry that are now used to manage physical waste elsewhere, they suggest.

In many ways, the ideas are easy to translate. Physical waste falls into four categories which translate easily into the virtual world:

- Unintentional data. Data unintentionally created, as a side effect or by-product of a process, with no purpose

- Used data. Good data that has served its purpose and is no longer useful to the user

- Degraded data. Data that has degraded in quality such that it is no longer useful to the user

- Unwanted data. Data that was never useful to the user

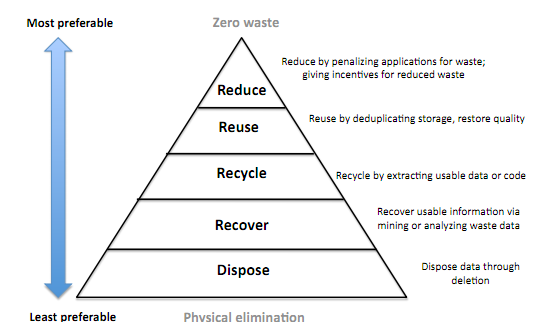

Why not apply the three Rs of conventional waste management to this virtual rot. In other words, use well known mantra of ‘reduce, reuse, recycle’ to better manage data

Hasan and Burns suggest that operating systems could provide incentives for applications to reduce the amount of waste files they generate, perhaps by reducing the I/O bandwidth or scheduling fewer CPU cycles to the worst offenders.

“This concept is equivalent to the Pay-as-You-Throw scheme and the polluter-pays principle used in real life waste management,” they say.

They also suggest setting up “digital landfills”, made of a semi-volatile storage medium that gradually degrade in time. “Unwanted data objects will fade automatically and the storage space can be reclaimed,” say the pair from Johns Hopkins.

It’s tempting to say that these ideas sound worthy but are otherwise impractical and unrealistic. But there are substantial benefits to be reaped from this approach, in particular for portable devices which are limited by battery life.

What’s needed, of course, is a hard core grass roots movement that campaigns for these kinds of changes and pioneers their use (just as the environmental movement has had for many years).

Perhaps this paper of Hasan and Burns will turn out to be the call to arms that this incipient movement needs.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1106.6062: The Life and Death of Unwanted Bits: Towards Proactive Waste Data Management in Digital Ecosystems

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.