A Vision through the Fog

In the arid Namib Desert on the west coast of Africa, the Stenocara gracilipes beetle survives by using its bumpy back to collect water droplets from fog and letting the moisture roll into its mouth. What nature has developed, Shreerang Chhatre, SM ‘09, wants to refine. The devices he hopes to build could help some of the 900 million people globally who lack safe drinking water or must fetch it from distant wells or streams.

“It’s terrible that the poor have to spend hours a day walking just to obtain a basic necessity,” says Chhatre, a Mumbai native who is a PhD candidate in chemical engineering, an MBA student at Sloan, and a fellow at MIT’s Legatum Center for Development and Entrepreneurship. While researching fog-harvesting devices, he is also developing business plans for deploying them.

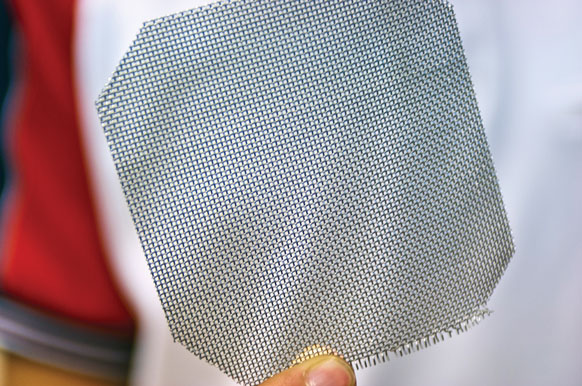

Interest in fog harvesting dates back at least several decades; government agencies in Chile and Peru started experimenting with the idea in the 1960s. Today’s devices consist of a large mesh panel on which droplets settle, connected to receptacles that collect drips. In one day they typically capture one liter of water per square meter of mesh. Chhatre has extensively tested refinements to the panels and believes he can improve their efficacy.

Chhatre’s research has focused on the wettability of materials, their tendency to either absorb or repel particular liquids (think of a duck’s feathers, which repel water). With Robert Cohen of the Department of Chemical Engineering and Gareth McKinley of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, among other researchers, he has coauthored three papers published in the journals Advanced Materials and Langmuir on the kinds of fabrics and coatings that affect wettability. The idea is to make sure that droplets land on the mesh and then quickly roll off once enough water accumulates.

Beetle physiology is an inspiration for fog harvesters, not a template: wind tends to drive water droplets off an impermeable surface like the beetle’s back, which is why researchers use mesh instead. “This kind of open permeable surface is better,” Chhatre says.

Turning the refined technology into a viable enterprise is the next challenge. “My consumer has little monetary power,” he says. As part of his Legatum fellowship and Sloan work, he is analyzing which groups could be customers for his potential product and identifying areas where it might work, such as the rural west coast of India, north of Mumbai. Or environmentally aware communities, schools, or businesses in developed countries might try fog harvesting to reduce the amount of energy needed to obtain water. “This is still a very open problem,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.