Early Astronomer Described Coriolis Effect Centuries Before Coriolis

In the century or so after Copernicus proposed the modern view of the Solar System, theologians and scientists lined up to criticise the theory.

Chief among them was Giovanni Battista Riccioli, an Italian Jesuit priest and an astronomer himself of some renown. Riccioli was one of the first astronomers to map the Moon, giving names to many craters that we still use to today. He was also the first to measure the rate at which objects fall.

Riccioli’s opposition to the heolicentric theory was not entirely dogmatic. He admired the Copernican hypothesis for its simplicity and even named one of the Moon’s craters for Copernicus.

But Riccioli believed he had good reason to dismiss Copernicus’ ideas. In 1651, in an encyclopedic work on astronomy called Almagestum Novum, he published 77 reasons why Copernicus was wrong.

Today, Christopher Graney at Jefferson Community & Technical College in Louisville, Kentucky, publishes a translation of some of these arguments (the originals are in latin).

It turns out that Riccioli’s thinking was ahead of its time. One central Copernican hypothesis is that the Earth must rotate, to explain night and day. Riccioli dismisses this with the following line of thought.

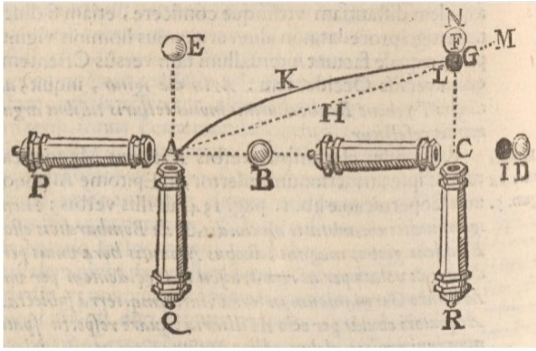

Imagine a canon at the equator, firing canon balls towards the north pole. If the Earth rotates, the equator is moving faster than the pole. So any canon ball launched from the equator would pass over slower moving parts of the sphere to get to the pole. The result would be the canon ball veering off course.

Riccioli argues that because this does not happen, the Earth cannot be rotating.

That’s a powerful argument. And Riccioli is entirely correct–the absence of this effect would be good evidence that the Earth is not rotating.

But as Graney points out, Riccioli is describing the Coriolis effect, an effect that influences motion in any rotating frame of reference. What Riccioli didn’t realise, of course, is how small this effect is.

Today, we know that the Coriolis effect plays all kinds of subtle roles on Earth, not least of which is in influencing the motion of weather systems. And today, gunners do take this force into account when calculating trajectories.

But here’s the thing: Gustave Coriolis, the French mathematician after whom the force is named, did his work on the subject in the 19th century, some 200 years after Riccioli.

So it looks as if this Italian priest was not just years ahead of his time; he was centuries ahead.

Amazing what you can find in these ancient texts.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1012.3642: The Coriolis Effect Apparently Described in Giovanni Battista Riccioli’s Arguments Against the Motion of the Earth: An English Rendition of Almagestum Novum Part II, Book 9, Section 4, Chapter 21, Pages 425, 426-7

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.