A Minority Report Interface for the Rest of Us

Gestural computing: ever since a be-gloved Tom Cruise blew everyone’s minds in Minority Report, interface dorks have been trying hard to bring it into the real world. But here’s the problem: who actually wants to spend their whole workday wildly waving their arms around?

Well, musicians and dancers just might. That’s the idea behind Toscanini, a gestural computer interface named after the famously gesticulative Italian conductor.

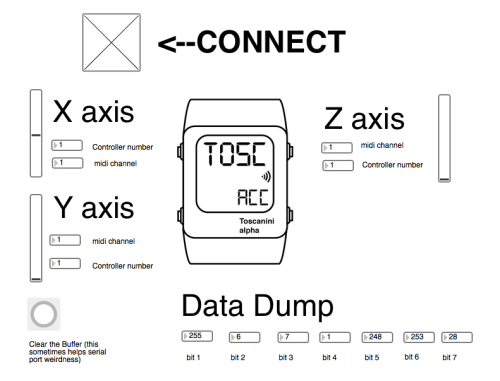

And here’s the best part: unlike those room-sized setups you’ve seen on TED talks, Toscanini fits a ramen-noodle-sized budget. The free software runs on Texas Instruments’ “Wireless Watch Development Tool” – an accelerometer-equipped, programmable sports watch that costs just $50.

So what the hell does it do? Basically, it provides a bridge between your movements and digital instruments like synthesizers and keyboards – or anything else you can control from your computer through a MIDI connection. Think of it like Microsoft Kinect, but for making weird performance art instead of playing Xbox.

“Currently it acts like a MIDI keyboard, except you can control the knobs with your movements,” says Lindsey Mysse, who co-created Toscanini during a 24-hour hacking contest. “But it doesn’t have to make music. It can control a mouse. You just put it on your wrist and make something happen.”

|

Granted, you’ll have to be something of a hacker to truly take advantage of Toscanini’s power – the software is in alpha and uses a visual programming language called Max/MSP. But that’s the whole point, says co-creator Robby Grodin: “Unlike Kinect or Wii, this is intended to be hacked. You can record your movements as musical ‘macros’, or build your own apps.”

Mysse thinks Toscanini will appeal to artsy types who wish to add an element of “true randomness” to their digital creations. “Gestural expression puts your personal imprint on the data,” he says. “It’s random, but it’s also you. 500 people can play three notes on a piano and not sound much different, but with our watch it will always sound very different.”

Mysse and Grodin are considering building a product ecosystem around the watch, including paid apps and musical accessories produced via 3D printing. But their near-term goal is appropriately bohemian: “We want to hook up with a dance company,” says Grodin. “That’s our dream.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.