The Hot New Thing in Biometric Security is… Ears

The tubular crest that runs over the top of your ear is known as the helix. It’s quite distinctive, even if it doesn’t posses the pointy bit that proves you’re descended from a monkey. Best of all, it doesn’t change as you age, unlike the iris, which along with the face are the most popular means by which machines recognize humans.

The problem with using ears (or any other feature, such as your fingerprint or even the way that you walk) for biometric security, is that first a computer must find and isolate the feature to be identified.

That sounds like a simple problem only because humans do it so easily. Feature recognition is one of the biggest challenges of computer vision.

Fortunately, researchers in the School of Electronics and Computer Science of the University of Southampton have come up with a means for identifying ears with a success rate of 99.6% (pdf). That doesn’t mean it can identify who owns what ear at that rate, just that it can successfully complete the first step of any biometric identification exercise, known as enrollment. (Recognition is, of course, the second step.)

If you’re into algorithms, the way they got such consistent results is no less interesting than the potential applications of their work. (Think Minority Report, but instead of keeping around his old eyes, Tom Cruise has to cart around his old ears.)

The researchers followed a burgeoning trend in image analysis in which the algorithm used to highlight a feature is based on some actual physical process. A classic example of this is the use of an algorithm in which every pixel is assumed to act on every other pixel with a gravitational or magnetic pull proportional to its intensity. Add up all those forces, and you get a vector field that uniquely represents the image.

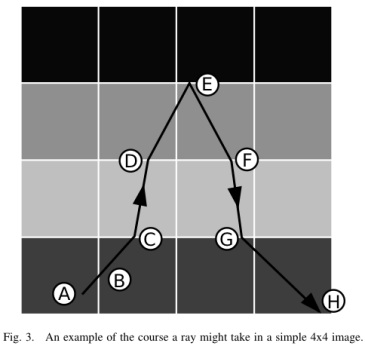

In this experiment, the researchers used the analogy of rays of light passing through the pixels to help them trace the helix of the ear. Depending on the intensity of the pixel, a hypothetical ray of light is either refracted by some angle or even reflected.

The advantage of using physical analogies to define vision algorithms is that they make intuitive sense and can be grasped by our puny human minds, allowing engineers to guess what the results of adjusting relevant parameters will be.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.