New "Ultra-Battery" as Energy-Dense as High Explosives

The energy density of batteries is tremendously important as an enabler of new technologies. Meanwhile, the scramble to create ever more powerful batteries has even led some manufacturers to contemplate powering cell phones with energy-dense hydrocarbons like propane.

This is why the claims made for an extremely early-stage “ultra-battery” recently announced in the journal Nature Chemistry are so remarkable.

“If you think about it, [this] is the most condensed form of energy storage outside of nuclear energy,” said inventor Choong-Shik Yoo of Washington State University. Yoo’s ultra-battery consists of “xenon difluoride (XeF2), a white crystal used to etch silicon conductors,” compressed to an ultra-dense state inside a diamond vice exerting a pressure of more than two million atmospheres.

Applying this level of pressure to XeF2 “metallizes” the substance, pushing all of its atoms closer together, into a new stable state.

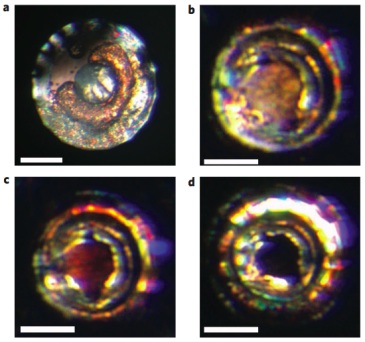

This figure shows how the crystal changes color as it changes states, from a relatively soft transparent crystal to a “reddish two-dimensional graphite-like hexagonal layered structure,” and then, above 70 Gigapascals of pressure, to a “black three-dimensional fluorite-like structure,” which is a metal.

In its ultra-dense state, the mechanical energy transmitted to the metallized XeF2 is now stored in the substance itself as a kind of chemical energy. All it takes to release it is a perturbation of a single atom in the crystal, which will cause the entire metallized substance to spontaneously “unzip,” says Yoo.

The reaction would be, quite literally, explosive. In an instant the XeF2 would turn its stored energy into thermal energy with almost 100% efficiency. The XeF2 stores about 1 kilajoule of energy per gram, or “about 10% of the energy stored in a rocket fuel of liquid H2 and O2 mixtures, or about 20% of [the energy stored in] one of the most powerful explosives, HMX,” says Yoo. When viewed as a potential energy storage medium, this discovery qualifies as “a new class of energetic molecules or solid fuels,” he adds.

Until we figure out how to build rocket-powered consumer electronics, the trick to turning XeF2 into a viable means for storing and releasing energy is to figure out what sort of impurities to add to make it “metastable,” just like all the combustible fossil fuels we are surrounded by, which we call plastics.

“If you think about all materials we know, 95% or more are in a metastable state,” says Yoo.

Metastability is a fundamental problem in materials research, and is common to many other substances that metallize and acquire exotic properties after being compressed to an extreme degree, including CO2, N2, O2 etc. If Yoo and his colleagues can conquer this issue for a common substances that can acquire a new molecular configuration at high pressures, they will have created an entirely new means of storing energy.

That goal is a long way off, however - so far Yoo’s discovery has only been synthesized in the lab, in amounts so tiny that when it “unzips” it poses no hazard.

![]() Follow Christopher Mims on Twitter, or contact him via email.

Follow Christopher Mims on Twitter, or contact him via email.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.