Cheap DNA sequencing will drive a revolution in health care

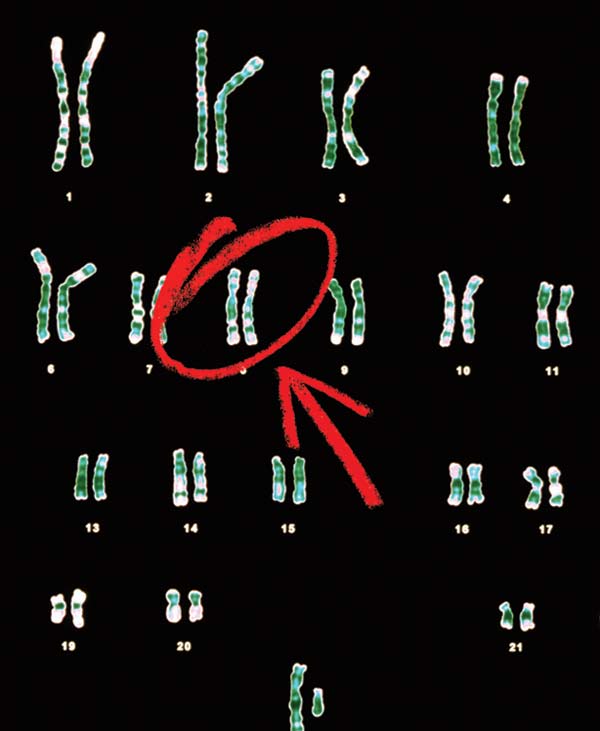

The dream of personalized medicine was one of the driving forces behind the 13-year, $3 billion Human Genome Project. Researchers hoped that once the genetic blueprint was revealed, they could create DNA tests to gauge individuals’ risk for conditions like diabetes and cancer, allowing for targeted screening or preëmptive intervention. Genetic information would help doctors select the right drugs to treat disease in a given patient. Such advances would dramatically improve medicine and simultaneously lower costs by eliminating pointless treatments and reducing adverse drug reactions.

Delivering on these promises has been an uphill struggle. Some diseases, like Huntington’s, are caused by mutations in a single gene. But for the most part, when our risk of developing a given condition depends on multiple genes, identifying them is difficult. Even when the genes linked to a condition are identified, using that knowledge to select treatments has proved tough (see “Drowning in Data”). We now have the 1.0 version of personalized medicine, in which relatively simple genetic tests can provide information on whether one patient will benefit from a certain cancer drug or how big a dose of blood thinner another should receive. But there are signs that personalized medicine will soon get more sophisticated. Ever cheaper genetic sequencing means that researchers are getting more and more genomic information, from which they can tease out subtle genetic variations that explain why two otherwise similar people can have very different medical destinies. Within the next few years, it will become cheaper to have your genome sequenced than to get an MRI (see “A Moore’s Law for Genetics”). Figuring out how to use that information to improve your medical care is personalized medicine’s next great challenge.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.